Integral culture

The Idea of Integral Culture

by Stephen Edred Flowers

I. Introduction

Our culture is sick. It has been undergoing a process of disintegration for a number of centuries now. Its various constituent parts have progressively been scattered and disconnected from their natural or organic moorings. Such disintegration can only be rectified, healed, as it were, by integration, or reintegration.

The word “culture” has somewhat irritated me over the years.

People seem to use it in a vague and ambiguous ways. When I began teaching world literature in translation at the University of Texas in the fall of 1984 I undertook a more detailed study of the term “culture”, with the intention of using what I found in my lectures. What resulted was the discovery of the “culture grid.”

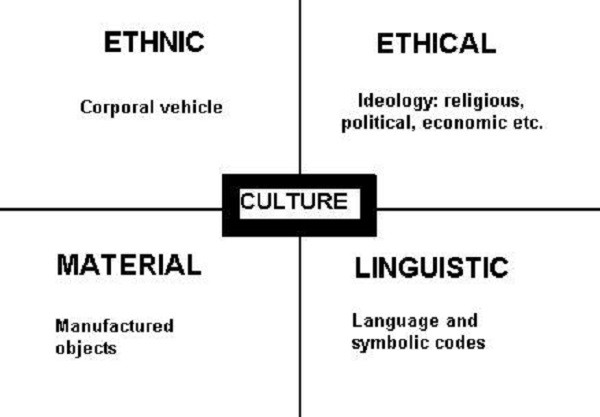

Culture is made up of a minimum of four different categories, each of which is essential to the whole idea of culture, and none of which can be ignored when trying to describe a culture in its entirety. These four categories are: ethnic culture, ethical culture, material culture, and linguistic culture.

In most previous discussions of these cultural categories, the emphasis has been laid on the existence of the four categories, and the necessity of each to a description of the whole.

This emphasis was good as far as it went, but it was rather static. In fact, what occurs in dynamic cultures is that the categories of culture are all constantly interacting with one another. There is a constant ebb and flow and interweaving of the categories, each of which serves to reinforce the others.

Our first task is to identify the constituent parts of culture, i.e., of the complete map of human experience and action. Then there follows the imperative to develop each of these categories intensely and to the best of one’s ability. Finally it becomes necessary to complete the circle by reintegrating the component parts into an organic and vital whole in which the individual will stand as a culturally authentic man. More importantly, the process of “completing the circle” serves to reinvigorate the culture itself.

This organic process is achieved by a conscious effort to integrate the cultural categories and thus reconstruct an integral culture. This must first be done on an individual basis before it can be transferred to a collective level. Cultural reintegration begins within.

At the conclusion of this article it will become apparent that if one is able to agree that the ideal culture is an integral one, and that individuals are really only truly free within the context of an integral culture, then a whole series of personal and collective imperatives follow. These imperatives generally run counter to the trends of modern life, which tends to disintegrate culture in favor of the apparent interests of the isolated individual. This individual, separated from his culture, then becomes an easy target for promoters of various transitory interests. These interests could involve a political notion, or a new consumer product, or any one of a billion other things. He disintegrated, atomized individual, cut out of his organic cultural context is relatively more susceptible to these suggestions than someone firmly rooted in a set of objective and conscious cultural values. Real cultural values of this kind cannot, however, be manufactured artificially. They must grow from deep historical soil.

II. Culture

In order to develop more fully the idea of integral culture, a more global understanding of the categories of culture must be attained.

The so-called culture grid appears in the illustration below. This grid shows the four cultural categories arranged in a way that suggests more meaning than the mere listing of them can convey.

The two on the left side of the diagram are primarily material in nature, while the two on the right side are mainly symbolic. While the two on the top tier might be considered to be primary, the two on the bottom tier are secondary.

All categories of culture involve contact between two or more humans. Ethnic culture is rooted in the sexual connection between a man and a woman which leads to the production of children.

The product of this union is the bodily vehicle for culture to manifest itself in the material world. Without this reproductive activity – the literal incarnation (embodiment) of culture – obviously no culture is possible. The body itself, in the form of DNA, is thought by many to encode certain cultural patterns, and it is also true that cultural data absorbed by the developing human (especially during the first few years of life) actually results in permanent physical changes in the brain. (See Brad Shore’s ‘Culture in Mind’, Oxford, 1996.)

The link that living individuals have with their ancestors is not only a symbolic one. It is also physical. The entirety of the bodies of our ancestors constitutes a sort of cultural hyper-body for us. Ethnic culture is embodied culture.

At the other end of an apparent spectrum is ethical culture. The ethos of a culture is its symbolism or ideology. This is perhaps the part of culture that most interests us, as we are usually most fascinated by the ideas of our own culture and others. This si the part of culture that contains structures, patterns, and myths (or meta-narratives) made up of symbolic ideas.

The words “ethnic” and “ethical” are chosen here, although other terms might have been used, to demonstrate the archaic link between biology and ideas.

To the ancient Greeks the ethnos or tribe was determined by the gods to whom one sacrificed, and hence from whom one got one’s values. Greeks were those who sacrificed to the Greek gods, spoke Greek language and perpetuated the Greek ethos biologically.

A similar pattern of belief can be detected in other Indo-European branches of the tradition.

Symbolic, or ethical, culture is entirely invisible and super-sensible. We know about it through its manifestations in the other three branches of culture: ethnic, material, and linguistic.

The symbolic culture is most perfectly encoded in the linguistic culture. This amounts largely to the language code spoken and understood by the members of a given culture. But the linguistic code, its phonology, morphology, syntax, and semantics also constitutes a complex semiotic code by which members of the culture understand the world and express themselves to other parts of the world. Without such communication between humans, and meta-communication between humans and other parts of the cosmos, humans would be impotent in the world.

Material culture is easily seen. It is made up of everything a culture produces, i.e., all the physical objects made by members of that culture. This could be a flint arrowhead, or a skyscraper. These are the objects made by the human and after having been imagined by the human heart. In other words these objects are artificial, i.e., “made by craft of man.” It is often the case that all we know of an archaic culture is is summed up in the objects it left behind. But from these objects we can often reconstruct the culture’s values. If modern culture were to be evaluated by its material culture alone, I am not sure what the archaeologists of the future would make of it. They would certainly find it titanic, but perhaps also sterile and empty.

One thing that should be obvious is that these four components of culture are not discreet and isolated categories. Rather they are four poles of manifestation which belong to a larger whole. Each category interacts with the other three in a lively discourse. Linguistic culture crosses the material in the form of writing, inscriptions, books, computer software, etc. Symbolic culture not only provides forms for the production of material objects (such as temples and sculptures), but also usually determines the nature of the physical reproduction of human bodies in the form of laws and customs surrounding marriage and child bearing and rearing. (The current general chaos and breakdown in these customs is just as much a statement on this topic as are the most traditional customs found in former times or in other cultures.)

The four basic categories of culture intersect and influence each other, and no one of them can exist without the other three. Changes in one will inevitably lead to alterations in the other parts. Vitality in one will help invigorate the others, while weakness in one will just as naturally result in the spread of this weakness to the rest of the whole.

In our current state of cultural fragmentation, this sense of the integrated nature of culture has been lost. The root cause of this fragmentation should also be apparent. One of the most effective ways in which to revolt against the modern world is to undertake the (re)integration of culture, to realize a personal and cultural synthesis – or “bringing together” – of the various categories of culture.

In order to undertake this revolt, one must begin with one’s self. The synthesis of the cultural categories within should be a harmonious one. That is, although humans are in a practical sense free to “mix and match” cultural elements, only fools would seriously suppose that they themselves were wise enough to design such a synthesis before they were virtually finished products of culture and character. It would be like asking a child to design its life when it was eight years old! In such a case we would not wonder at why a such person would be very unhappy at twenty years of age. One’s individual cultural synthesis theoretically exists in potentia. It is the work of the individual to realize this, to make it real, to actualize the potential.

This pre-existing cultural synthesis, to which we strive to return on a higher octave, can only have its in a time when an integrated whole was in evidence. This is why individuals interested in cultural authenticity so often yearn for a pagan or archaic times. It is not so much a longing for “paganism” per se, as it is a longing for the wholeness and integral nature of the self and culture which is possible in such societies.

On a personal, individual, level it is the practitioner of integral culture to discover and then to harmonize the contents of his body, brain (mind), tongue (language) and his deeds or daily actions. Each part of life takes its clue from another integral part of that multidimensional life. The body contains a code which bears the essential story of all of one’s ancestors. One’s cultural myths articulate these, and these myths are re-encoded in actual tales expressed in often archaic languages. These codes bear the blueprint for inner action which can lead the individual back to an integrated state of being. This is how they functioned in former times, and this is how they can function today. Merely reading and thinking about these patterns is usually not enough. Other techniques designed to imprint the codes on the conscious mind must be experienced. High levels of repeated, concentrated, ordered and intense thought must be experienced. This is not the place to enter into these techniques.

An essential part of the process of culturally re-integrating the personality involves conscious interaction with others belonging to that culture. Culture is, in the final analysis, always about interhuman contact. Isolated individual experience is a form of mysticism, but not a manifestation of integrated cultural activity. One must determine for oneself how one can best contribute to the task of cultural integration, or allow it to be determined by others. Some will provide strong human bodies for the future, others will create institutions that will re-invigorate and carry culture along, others will teach the lore and languages of the culture, others will shape and craft the artistic and practical tools that bear the culture materially. Some noble souls will be able to contribute in more than one of these areas. But all of these realms are necessary; no one is really more important than the others. They must all be seen to work together as a whole.

It might be noted that all of the ideas of culture are seem to be somehow rooted in the “past”. In order to understand the idea of the “past”, the idea of history itself must be examined.

III. A “History” of Ideas

Depending on how it is understood, the concept of “history” can either be irrelevant or essential to the idea of integral culture.

If by history one means an objective string of events progressing from the distant past to the present moment and endowed with “cosmic” meaning and significance, then “history” can be dismissed as “bunk”. History has never been, nor will it ever be, some sort of scientific pursuit limited the “hard facts”. History is what it says it is: a story. All stories are narratives. To have any meaning at all they have to have certain characteristics of morality, tension, and most especially certain “plots” which are inherently interesting to the listener or reader. These latter characteristics show just how much “history” is only mythology recast in a secularized mode. There is nothing wrong with this, aside from the deceptions that might be fostered if people were to believe otherwise – which of course most people do. This is due to the fact that the myth, or meta-narrative, of the modern world within most people live today has as one of its mainstays the idea of an “objective history.” (This is a meta-narrative inherited from Judeo-Christianity, which was the first ideology to sacralize mundane historical events and endow them with cosmic significance.)

On the other hand, if by history we mean a synthetic view of myths, structures, and ideas as well as various events viewed over time, then “history” is fundamental to culture.

Mircea Eliade never tired of pointing out that myth seeks to destroy history. That is, myth is eternally true and recurrent, due to its inherited structural characteristics. History, as commonly understood, however, was supposed to be provisionally true, inevitably open to various interpretations, and fundamentally chronological and progressive. Myth is eternally true, whereas history is often a celebration of the absurd. French thinker and critic Alain de Benoist, among others, have pointed out that the past, present and future are not, in reality, a linear progression, but rather three entirely different dimensions of human existence. Other ideas, such as those of Oswald Spengler, emphasize the “morphology of history” and see cultures are organic subjects of “history” bound by cyclical laws of birth, life, and death.

Although it is most certainly a meta-narrative, or myth, in itself, it is nevertheless useful to review the ordinary historian’s idea of the progression of epochs in the history of European ideas.

The time prior to the advent of Christianity is lumped by historians into a period they call “ancient”. They don’t know what to do with it in the larger sense, as these is no one overriding myth or general theory in terms of which it can be understood. The Indo-Europeans (and all their cultural branches) had their own set of values, the Egyptians theirs, the Chinese theirs, and so on. An intelligible plurality reigned and ethnic labels sufficed to differentiate cultures in a more general sense as well: We can speak of Germanic people, religion, art objects, and language as a more or less coherent and integrated whole. The same goes for the Greeks, or Celts, or any of the other branches of the Indo-European tree. Of course, it is equally true of all other “ancient” cultures. We confront a curious situation, however, when we examine cultures of continuous authenticity: be they found in India, or elsewhere. Certain cultures suffered no major breaks between their archaic pasts and their present states. However, the majority of cultures have endured major disruptions in symbolic continuity.

This disruption is identified at the points the ruling paradigm shifts from the particular and culturally authentic one to a more generalized (international) one. This generalized paradigm is most often characterised by monotheism, e.g., Christianity or Islam. With the advent of this paradigm in a culture, no matter how partial and imperfect the advent was, it is said that the culture has entered into a new phase. In Europe this new phase subsequently came to be called the “medieval” period, or the “Middle Ages”. Anything in the middle comes between two things. In this case these two are the “ancient” and the “modern”. The Middle Ages were dominated by the myth of faith as institutionalized in the Church. This is not the place to discuss the merits of this myth. It is only important here to realize that the various plural and nationally determined mythologies were at least partially replaced by a single and “international” one. Although much is often made of the transition between the medieval and the modern period, the differences between medieval and modern mythologies are not nearly as great as those between the ancient and either the medieval or modern.

Modernity merely replaced one monolithic myth with another. Instead of faith and the Church being the highest arbiters of the truth, reason and science took the helm. Often medieval “religious” values were merely secularized and repackaged “political” models. The Church promised the salvation of all of humanity through faith, whereas scientism, humanism etc. promised the same sort of universal perfection through the progressive application of reason.

Those who criticize the monotheosis of both the medievalist and the modernist, those who see malevolent foolishness in the promises of both faith and reason – as embodied in the ideologies of the Middle Ages and the “progress” of modernity – can be called “postmodernists.” It should be noted that the term “postmodernism” has generally been hijacked by campus Marxists and crypto-Marxists to further their own agendas (which are usually related to their own career advancements at universities, not the last bastions of the Marxist faithful). For this term it is difficult to use the term without invoking alongside it a whole host of “politically correct” fables.

IV. The Idea of Integral Culture

In the context of modern meta-narratives the most effective revolt would be one which challenged the the modernistic atomization – the splitting up of all integrated units into their smallest parts for the sake of homogenizing them politically and/or economically – by promoting a reintegration of cultural elements or categories in a harmonious and authentic whole. From what has been said perhaps a good idea of how this can be done has already been understood. However, in conclusion, I would like to be more specific.

There are certain pathways or paths of action toward integral culture. These are not alternatives or options but rather things which must be, to one degree or another, integrated in one’s life. The first is tradition, the other personal authenticity, and the third cultural action.

Tradition is that which has been handed down from time immemorial along various pathways: genetic, mythic, linguistic and material. The subject, i.e., doer, of this kind of action must discover the tradition, myth and school to which he or she belongs.

This is not a “choice” in the sense of being something that is entirely arbitrary. It is a realization of a truth. Once this authentic choice has been made, which can just as easily be seen as an “election” by some aspect of that tradition, one can never go back or waver from the implications of that realization.

The reason for this is that it is a matter of personal authenticity. Modern people seem to think that they can choose to become something which they are not in reality, e.g., an Amerindian shaman, or a Kabbalistic mystic. But one can never truly become that except in one’s own imagination, (and perhaps in the imaginations of others). In truth, we can only, to paraphrase Fichte, become who we are. Within that realm of possibilities is an infinite number of directions, but the tradition is a fixed one. The modern world makes the path of discovery of an authentic tradition almost impossible. Yet a few have persevered, in hopes that some day the door will be opened for the many. One must simply ask oneself: “Of what can I be a ‘first class’ exemplar?” Can I be a first class Amerindian shaman? No, an Amerindian can be that. Can I be a first class Kabbalist? No, an orthodox Jew can be that. The positive answer to this question can be many things. But in one’s own heart, if the honesty of that answer is complete, the authentic awakening will be unmistakable and irrevocable in life. The true path will be opened, but it will be far from accomplished.

The third component in the path toward integral culture involves interaction with others. One must participate actively with others within the same school or tradition, with others who have similarly discovered their authentic path. Being taught by others, teaching others, creating in cooperation with others, and in general interacting in any and all ways possible with others from the same tradition forms the quintessential laboratory not only for broad cultural action, but inner personal work as well.

This approach to individual development necessarily takes more into account than one’s momentary and transitory desires. It views the individual in his or her true context, as a being that exists in many dimensions, past, present and future simultaneously. The individual has a history, in the sense that the individual only exists as a part of a stream of culture which cannot be understood apart from its constituent events and structures. The reconstruction of culture on the model of a healthy, integrated view of society could not help but have a beneficial effect on interpersonal relations, and hence on all aspects of culture.

The deep and subtle malaise of the modern world has its roots in disintegration and promotes it at every turn. Such rootlessness is marketed under noble terms like “freedom” and “individual rights.” But once the tree has been uprooted and killed by the onslaught of progressive modernism, and by the time those living in the tree have realized what has happened in the name of “individual freedom,” it is already too late. The eternal good of the whole has been sacrificed to the ephemeral appetites of the individual. How then can the individual mount a revolt against this modern world?

Cultural disintegration is countered by cultural re-integration. The return pathways to this level of being are marked with the signs of tradition, authenticity, and action.

Without these no effective revolt is possible.

Sic semper tyrranis!

Source:

Tyr: Myth, Culture, Tradition vol. 1

Tags: integral culture, integralism, stephen eldred flowers, tradition, traditionalism