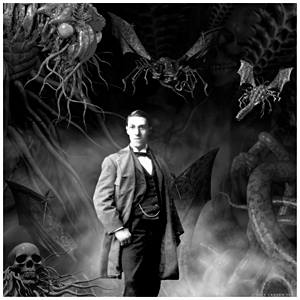

In Memorial of H.P. Lovecraft, the Philosopher of Terror

Howard P. Lovecraft died March 15th, 1937 and his fiction about the terror of the great beyond is less of a fantasy and more of a warning.

The predominant philosophers of the 19th century spent their time imagining and theorizing about the limits of our world and the extent to which we humans can explore those limits. H.P. Lovecraft wasted none of his time on that and instead cut straight to the chase and told us unflinchingly what exists beyond the limits of our perception.

In Lovecraft’s cosmos, the world beyond is a world hidden within our own world. We pass through it as it passes through us, but we can never know about it or see it. Unless, of course, we are properly attuned to it.

German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724 – 1804) is one of the pre-eminent thinkers in philosophy, and one of his views on human perception is called the Two Worlds View or “dualism.” In this outlook, there is the world that our sensible intuitions present to us, and then there is the Thing in Itself. The Thing in Itself has also been called the Absolute. We can never know the Absolute because our faculties of intuition are limited, and we can only know an object and the world around us as well as our senses represent the object to us. Because of this we will always be ignorant of any absolute truth.

For in this case that which is originally itself only in appearance, e.g., a rose, counts in an empirical sense as a thing in itself, which yet can appear different to every eye in regard to color. The transcendental concept of appearances in space, on the contrary, is a critical reminder that absolutely nothing that is intuited in space is a thing in itself, and that space is not a form that is proper to anything in itself, but rather that objects in themselves are not known to us at all. – Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason

Reading Kant is not easy. Depending on who you ask, German philosophy has killed more people than the electric chair. Nobody knows if it is because of the dense text or if it is because of its tendency to invoke existential crises in readers. If you are faint of mind, then I suggest you return to reading more tame philosophy from a more contemporary thinker like Dr. Suess.

For those who wish to brave the brinks of existential terror in Kant’s philosophy, then the Two Worlds view would lead to the logical conclusion that everything before us is merely an illusion. It’s an easy enough of a mistake, but Kant would prefer to have us believe that the Thing in Itself is real, and that we shouldn’t take everything before us as an illusion. Considering Kant’s hopes and also his propositions about the nature of objects and the painfully limited nature of our sensible intuitions, I don’t know which is more terrifying — the possibility that everything we see is an illusion, or that there are unknowable objects that will forever confound our senses and intuitions.

But, is it desirable to have access to the Absolute, and can we learn anything from it?

German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (1788 – 1860) would disagree. Schopenhauer was properly steeped in Kant’s philosophy, and he was renowned as the philosopher of pessimism. We all know what Schrodinger did with his cat, but if Schopenhauer had a cat it would be Grumpy Cat. If that doesn’t put things into perspective, just know that there wasn’t a more pessimistic thinker in all of history than Schopenhauer. But, as Schopenhauer says, if we could overcome the limitations of our own cognitive abilities and sensible intuitions then we should be able to encounter the vast gulf of the incalculable infinity that is all around us.

If we lose ourselves in the contemplation of the infinite greatness of the universe in space and time, meditate on the thousands of years that are past or to come, or if the heavens at night actually bring before our eyes the innumerable worlds and so force upon our consciousness the immensity of the universe, we feel ourselves dwindle to nothing as individuals, as living bodies, as transient phenomena of will, we feel ourselves pass away and vanish into nothing like drops in the ocean. – Arthur Schopenhauer, “On the Inner Nature of Art,” from The World as Will and Idea

This is what Schopenhauer calls the Sublime. The sublime is what we feel when we are encountered with something that exceeds the limits of our senses. When we are faced with the sublime, our senses of reason and comprehension are suspended; our capacity to reason and communicate become ineffective. The sublime is not something which is simply inconceivable to us, or something which confounds our reason. The sublime is not a mysterious puzzle to which we cannot find the solution. The sublime is terrifying because it is impossible for our senses to completely register, and it completely overwhelms our senses in a forceful and uncompromising assault.

The Thing in Itself and the Absolute are completely beyond our sensible intuition, and thus must fall entirely within the realm of the sublime. Access to the Absolute would be nothing less than complete absolute mind-bending terror.

This is where Lovecraft comes in.

While the other philosophers were busy trying to draw the line at where our senses would stop perceiving the given world, and what it would feel like if we could have access to the Thing in Itself or the Absolute, Lovecraft told us what it would look like.

Imagine if we had a machine like the one from Lovecraft’s story “From Beyond”, one that could pull back the veil of ignorance which we live under, and reveal the true nature of the things that we encounter world…

‘You see them? You see them? You see the things that float and flop about you and through you every moment of your life? You see the creatures that form what men call the pure air and the blue sky? Have I not succeeded in breaking down the barrier; have I not shewn you worlds that no other living men have seen?’ I heard him scream through the horrible chaos, and looked at the wild face thrust so offensively close to mine. His eyes were pits of flame, and they glared at me with what I now saw was overwhelming hatred. The machine droned detestably. – H.P. Lovecraft, From Beyond

There are only two options when we are faced with the Absolute. It will turn us stark raving mad, or cause the urge to break from contact with the Absolute in a complete panic. In no case is it desirable to have contact with the Absolute, and we should be thankful that our senses restrain us from encountering it.

Is ignorance bliss? Perhaps, but a life of ignorance and apathy will be the death of us all.

Tags: absolute, dualism, h.p. lovecraft, howard phillips lovecraft, immanuel kant, monism, thing-in-itself