Forest Poetry: Collected Writings

On the Virtue of Prayer

Mysticism is often regarded as pure metaphysical speculation without any possibility of experience beyond the constitution of the mind. This misconception arises from lack of real experimentation among those who would make such a judgment, who in consequence judge mysticism only as a group of philosophical assumptions. Metaphysical theory, although not empirically demonstrable, can be transformed in a subjective, and yet authentic, experience by people with an honest and ardent desire for Truth. How can we achieve certainty? How can we discover the Truth in all metaphysical speculation?

Religion is more than an institution with the ability to bind communities, but also a bastion of sacred literature and successful methods of knowing God. This method of spiritual recognition has two inescapable and mutually inclusive sides: on one hand ethics as a guide for behavior for the external, material world, and on the other hand a contemplative exercise for inward, spiritual experience. In order to know the Divine, beyond all the acknowledged metaphysical theory, both these interdependent and indivisible aspects must be present within a given religion.¹

What exactly is this contemplative praxis? Very simple: Prayer. Now, Frithjof Schuon divides prayer into two basic modes: canonical prayer, and meditation. Canonical prayer is the reciting of sacred texts or orthodoxly defined prayers, in contrast with the personal prayer that is a spontaneous message from the individual to God. While personal prayer is good and also advisable, both canonical prayer and meditation have transpersonal qualities that allow man to “listen†to God in a state of quiescence, allowing him to discern the Truth above individualistic aspirations.

The main goal of prayer is to make man sensitive to the everlasting bliss of God. Even when there are well known benefits to prayer at a psychosomatic level, as well as many persons who, in their individual orisons, ask God for their personal needs, the true seeker conforms with no less than the sublime knowledge, and once attained even in a small proportion, will not desire anything less. We must remember this too: “But seek ye first the kingdom of God, and His righteousness; and all these things shall be added unto you.†(Matthew 6:33). Another way to say this is that in an esoteric approach, the real purpose of prayer is not to help the individual to make him materially successful, not even to relief him emotionally, but to resurrect the attention of his higher self to the spiritual world.²

Every material event must be recognized as transitory, independent of its emotional effect on us; as common humans, we can’t force our ego to be totally unaffected by worldly activities, but we can know our higher self which is beyond the ego, and thus command the ego with more accuracy. Also, we have to be especially aware of such events that are relatively beneficial to us, because they can cause us to deviate from the sacred path in the temporal satisfaction they bring. It is not about surpassing the unfavorable circumstance through prayer, but to surpass every egocentric circumstance, whether mental or physical.

In this ego transcendence (the Unio Mystica of Catholicism, the Hindu Samadhi, the Kensho of Zen) the practitioner overcomes the primordial duality subject-object, allowing his soul to exceed his circumstantial aggregate that defines him and separates him from the Absolute. Prayer permits the mind itself to know about the soul’s rejoicing in the divine fusion. This correct ordination between the mind and soul allows the mind to remember the mystic experiences of the soul, although this process can only be experienced and fully understood by the soul itself.

To exemplify the precise state that we want to attain, we cite Schopenhauer:

“It is then all the same whether we see the setting sun from a prison or from a palaceâ€.

What truly matters is the contemplation of the Intelligence. The material world is convulsive, especially in our modern age. In ignorance, a man becomes very vulnerable to its hardships and recompenses, and easily becomes a capricious person. In ignorance, Man confuses transitory pleasures with divine fullness, and becomes eager to insult God when fortune abandons him. In this situation, Man is not aware of God, but only aware of his own conditions or requisites to love God.

For these reasons, religions recommend to pray daily, whether it is the Catholic Rosary or the practice of Vipassana, as a virtuous habit independent of the eventualities of our lives.³ Prayer must be consistently practiced with patience and fervour in order to achieve, in life, the highest reward of all that lies in faith.

¹The ritual stands between the material action and the contemplative exercise, and it serves to be socially symbolic when public. Thus it is conferred practicality, although it may also provoke an internal, spiritual experience for the attendant. These rituals very often include collective prayer in them, with their social significance as part of the rite. However, individual prayer remains as the specialized exercise of contemplation. â€But thou, when thou prayest, enter into thy closet, and when thou hast shut thy door, pray to thy Father which is in secret; and thy Father which seeth in secret shall reward thee openlyâ€. (Matthew 6:6)

²The most common objection to contemplation and prayer on behalf of materialists is that they are nothing but ways to avoid action. Wrong. Mystic contemplation develops the right ordination of all human components in order to equip the individual to perform the best and noblest acts. The religious man perceives the sacred with his spirit and then acts in the material world with wisdom. As has been already mentioned, contemplation is not possible without a strict observance of behavior, and they both require high degrees of discipline; both are more in line with heroism than passivity. The Taoist concept of Wu Wei (no-action) refers to the ego renouncing its isolated, individualistic decisions in order to embrace the flow of Tao, in the same way that the Christians seek for the Logos to act in them. Therefore, in a spiritual sense contemplation is not in opposition to action or movement, but in opposition to the individualistic actions of an ignorant ego, ignorant of the Truth that is upon it. “One cannot remain without engaging in activity at any time, even for a moment; certainly all living creatures are helplessly compelled to action by the qualities endowed by material nature†(Bhagavad Gita III, 5)

³There’s a single transcendental aim for all the creeds, but nonetheless it is not advisable to mix techniques from different traditions, because every technique has a direct correspondence with the orientation of its particular Religion. Of course, it is convenient to investigate the different orisons or meditation techniques within a given tradition to find that which is effective for us, but we can’t detach the significance that a certain Religion brings to our corresponding natures simultaneously in both ethos and contemplative praxis.

Monotheism

A monotheistic religion is one which revolves around a single God. Usually monotheism refers specifically to religions of Semitic origin (Judaism, Christianity and Islam). The word itself, however, directly implies that which is essential to all religions and metaphysical doctrines, the Absolute. This inner meaning is actually a secondary consideration when using the term monotheism, which in general usage is only useful in referring to the more specialized point of view of the Semitic religions. Monotheism makes two basic demands of all men, firstly faith in God, and secondly an actualization of this faith in every aspect of life. These two demands are outlined by Jesus Matthew 22:34-40, and form the fundamental principles of spiritual life within the sphere of all the major religions, monotheistic or not.

The point of view of monotheism is firstly that, at the point of contact between man and God, God must in some respect be “humanized”. This is taken to its logical extreme in Christianity (in the incarnation of God in Christ), but is always present in the monotheistic traditions. This must not be understood to mean that these traditions place an arbitrary limitation on the divine, but only that God always appears to man in a form that man can understand, and it is the limitations of man which determine how God must appear to him, given that God himself is unlimited. The monotheistic doctrines then, at least in their outward form, are anthropomorphic.

The clarification of esoterism in the monotheistic revelations occurs in the continuity of Tradition, which has produced numerous commentaries which shed light on the mysteries of the scriptures. This is particularly valuable for those within western forms of Christianity, because the full metaphysical implications of Christian scripture no longer occupy a central place in the concerns of most western religious institutions. The theological knowledge and the forms preserved in the Catholic Church should not be overlooked in this regard, even though their intellectual dimensions are for the most part ignored. Within the sphere of Christianity the practice of Hesychasm amongst eastern monks preserves metaphysical contemplation on the scripture. For those who do not have access to this tradition the works of esoterists such as Pseudo-Dionysius, Dante and Meister Eckhart may provide some insight, but they cannot replace traditional continuity proper.

The clearest formulation of monotheism occurs in the Islamic saying, “There is no God but God” (LÄ ilaha illa al-LÄh). This is equivalent to the doctrine of non-dualism in the Advaita Vedanta school of Hinduism. This is because in esoterism the saying can also be formulated thus,” There is no Reality except the sole Reality”, which is the inward meaning of the Islamic version. The anthropomorphic implication in monotheism, as we have already said, corresponds merely to a limitation in human understanding. In reality this human appearance is an aspect of God who is the sole Reality. God is necessarily One, and Reality means oneness. To say Reality is also to say Infinity, or All-Possibility, and it is this Infinitude of Reality which necessitates the realization of Reality within the clothing of forms. Each of these forms is an illusion insofar as it is considered to possess some reality of its own, but each is also a symbol which reveals some aspect of the Divine. Thus the poles of subject and object are formal illusions. Absolute Reality cannot be more or less than perfect Unity.

This brings us to the second part of the Islamic formula, “Muhammad is the Messenger of God” (Muhammadun rasÅ«lu l-LÄh). Whilst the first part of the Islamic formula concerns God as such, the second part concerns God symbolized in a limited form. Together these two statements constitute the fundamental principles of metaphysics. We might also say in connection with this, that the difference between the Islamic and the Christian point of view, is that Muslims are concerned primarily with the fact that the symbol is not God, whereas Christians are firstly concerned with the fact that the symbol is God. These points of view clearly contradict each other exoterically, but metaphysically they are easily reconciled. The symbol is not God insofar as it constitutes a limitation, on the other hand it realizes God perfectly within the limitations of its own level of existence, hence at that level of existence it is God. For the Muslim every form constitutes a distraction, hence the abstract nature of Islamic art, whereas for the Christian, a particular form is the light which reveals the path to God. This is clearly demonstrated in the icon art of the Orthodox Church, which would no doubt be reviled by an exoteric Muslim.

Christian doctrine, unlike that of Islam, is primarily concerned with a symbolic figuration of the Divine. Trinitarian theology corresponds to the eternal ternary of Sat, Chit and Ananda (Being, Consciousness, Bliss), despite the fact that Christians are usually concerned with a microcosmic manifestation of this ternary. In the Trinity, the Father is the eternal Godhead, or Beyond-Being, in this sense the Father is the ‘absolute Absolute’, and is therefore beyond duality, however the Father is also Being, the creative Principle that begets the cosmos, and the Holy Spirit is the feminine Substance which receives Him, having its personification in Mary and Jesus Christ, who is the prefiguration of the entire cosmos. In another connection Christ is also the universal Intellect, or the immanence of the Principle in creation, and although this Intellect is crystallized in Jesus Christ, it is also present in every thing that exists. It might be said that an intellectual intuition is the presence of Christ in man, or more accurately man’s remembrance of his Christ-like nature, which is always present virtually if not actually.

For the monotheistic man God is the object of Love and therefore of devotion. This is not changed for a man who possesses intellectual knowledge, and in fact knowledge of God necessitates a greater devotion than that of the man who knows nothing and yet believes. Metaphysical certitude still requires a certain affective attachment to God through traditional forms of worship, otherwise it is nothing. The only type of man who does not require such spiritual supports is the man for whom metaphysical knowledge becomes actualized, and therefore God becomes the Subject rather than the object. In this case the individual no longer plays any part. Unless this is the case it is of utmost importance that men who possess theoretical knowledge, which is still certain because of its metaphysical character, do not become proud of what small knowledge they have attained. Monotheism demands humility. Man must acknowledge his need for God and give himself to God utterly. To the extent that he is capable he must actualize all of the knowledge which is given to him by God, and in doing so his actions are sanctified. The sufficient reason for monotheism is that it requires man to recognize his obligations to God.

Man’s Place in the Cosmos

Proponents of modernity often relate with glee how science has shown traditional concepts of man and the cosmos to be materially and demonstrably false. In some cases they even claim that the latest scientific theory represents an improvement not only in physical understanding, but also in moral understanding. For example, many traditional cosmologies posit a geocentric universe (for the purpose of this article we will solely reference the Aristotelian theory, because it is the most well known in the west, and the one against which modern scientists have specifically argued). The advent of the theory of a heliocentric solar system, and eventually of a universe without a true center, is often presented as replacing an incorrect physical model and as combating the hubris of man to place himself at the center of all things.¹ Some seem to think that when Aristotle placed the earth in the center of his physical model he did so because his “primitive” conceptions could not allow him to imagine a universe where man was not of the utmost importance, and that the modern models, by making man’s abode just one of a countless multitude of peripheral specs driven about in various cycles, made him more humble. This idea is completely false, and is in fact an inversion of the truth. It is the modern model that loftily exalts man and gives him delusions of grandeur, and the ancient model that situates man in his proper place in reality.

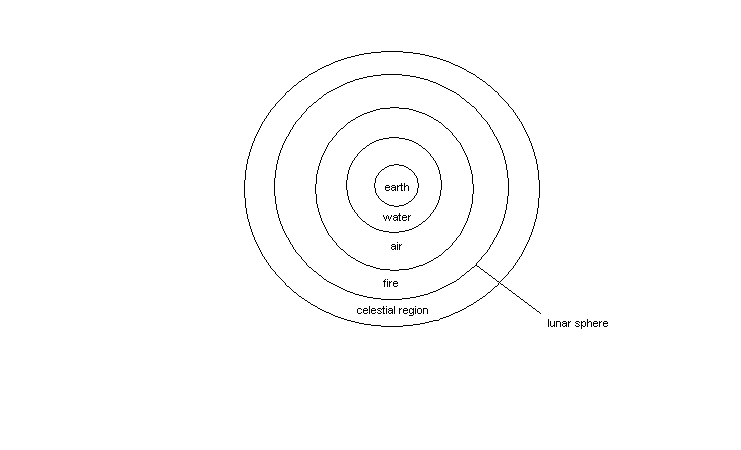

To understand this it is necessary to examine why Aristotle places the earth at the center of the universe. According to Aristotle the physical world is made up of four principal elements: earth, water, air and fire. In our daily experience we encounter these elements when they are mixed with each other in varying proportions, producing the variety of objects that contain more than one element. However, when an object is destroyed through burning, the fiery part and the earthy part are separated. The fiery part leaves the earth and travels upwards, while the earthy part, now in ashes, stays below. Each of the four elements has different qualities, and because of these qualities each element has a natural place in the universe. The most common qualities assigned the elements are as follows: earth is dry and cold, water is wet and cold, air is wet and hot, and fire is dry and hot. As already mentioned, during combustion, once it has been freed from mixture with the other elements, the fire moves upwards of its own accord, naturally moving above earth, water and even air. Earthy objects sink when placed in water, and water falls down through the air. Thus the elements naturally arrange themselves in this order: earth is the lowest, then water, air, and fire. Aristotle’s universe is spherical in shape, and the earth and mixed objects in which the element earth dominates the other elements are concentrated around the center. There are then the seas and lakes on the surface of the earth, the air surrounding the earth, and a layer of fire surrounding the air. Above the sphere of fire there is the outer sphere of the heavens. This outer sphere contains the stars and is made of a fifth element, aether. Aether, while also an element, is fundamentally different from the other four. It possesses a much higher degree of perfection, and unlike the other elements, it is incapable of vertical motion. Fire naturally has a place above the air, but it can be forced down to the earth. Similarly, a stone naturally rests on the earth, but it can be projected into the air. Aether, on the other hand, cannot exist anywhere other than in the highest sphere, cannot be mixed, and can only move in a circular motion, which it does as the stars circle around the center of the universe.

Before continuing with Aristotle’s model of the universe, we feel it necessary to insert a brief note concerning the doctrine of the elements, as it can be difficult to understand its true meaning. This doctrine can be obscured when the elements are solely identified with material objects. It is more accurate to view the pure elements as principles. For example, the element earth is not any particular piece of earth, nor is it the sum of earthy things. Rather it is the essence of solidity and heaviness. All material things that possess solidity and heaviness can be said to be “made” of earth, the heavier and denser they are the more their composition is dominated by the earthy element. Similarly the other elements represent other essences. This is by no means a full elucidation of the doctrine of the elements, but hopefully it will allow an easier understanding of Aristotle’s universe, and combat the idea that the doctrine of the elements is primitive or inferior.

Returning to Aristotle’s model, he describes the aetherial sphere as being the most perfect level of material existence, and uses the fact that it moves in a circle as part of his argument. Aristotle divides all motion into three categories: motion in a circle, motion in a straight line, and motion which is some sort of mixture between the two. Circular motion, specifically the circular motion of a circle or sphere, is the most perfect and most excellent motion, because as soon as it is in motion it is perfectly fulfilling that motion. A motion in a straight line starts at one point and ends at another, and changes position over time. The object moving with such a motion fulfills the different parts of this motion at different times. The motion is not complete until the object has reached its goal, but at this point the motion itself has ceased to be. The motion is imperfect, because as long as it persists it is striving after something that it does not have. Once the motion reaches that which it is striving after, there is no longer any motion. In contrast, the circular motion of a sphere is not moving from one point to another. At any one instant of its motion the goal of the motion is reached, and is reached perpetually at every instant of motion. Thus the motion is perfected (literally, completed) as soon as it begins. The motion cannot be without being perfect with respect to its own definition, as the perfection and goal of such circular motion is simply to be in motion, not to reach a goal.

Beyond the outer sphere of the heavens there is no physical existence, no space and no void. The only things that exist beyond the heavens are the eternal, unchanging, and incorporeal powers that govern the universe. Among these is Aristotle’s famed “unmoved mover.” This is the principle and source of all motion, but is itself incorporeal and hence unmoving. This unmoved mover possesses an even greater degree of excellence and perfection than the aethereal sphere, as it is infinite in power and absolutely unchanging. It first produces the circular motion of the heavenly sphere, as this is the most perfect motion, and subsequently all inferior motions. Earth, when unmixed and gathered around the center of the universe, is also in a state of rest, but this does not mean that it is similar in any way to the unmoved, incorporeal essences that exist beyond the physical universe. Earth cannot cause motion in itself or in other things, and is at rest because of impotence and sluggishness, not because it has a nature so excellent as to make it exempt from motion. A final important aspect of Aristotle’s model is that in relation to the rest of the universe, the earth is incredibly small in size, almost like a mere point.

Thus in Aristotle’s model of the universe there is a hierarchy from the more to the less excellent, beginning with the unchanging and eternal incorporeal essences, proceeding to the eternal but changing stars, then to the gross elements, and finally to earth, the lowest and most debile. It hardly seems like the earth is placed at the center of the universe in order to exalt it or its inhabitants. Rather the model stresses that man as a material organism and the entire physical world is lowly and insignificant when compared with eternal essences. The size of the earth shows that the material world is insignificantly small compared with supernal powers. Material things are completely governed by the incorporeal, and material things are bound by their very nature to be at the center, at the point farthest away from the divine. It is also now apparent that it is the modern theory that exalts man’s position. The modern worldview posits that there is no qualitative difference between different parts of the material world, and that earthly biological existence and the existence of a star are both physical reactions operating according to the same laws. In the modern view there are things in the universe greater than the earth in magnitude and physical power, but not in quality. Hence, to modern science, man and his world are equal citizens of the universe, rather than members of a divine hierarchy.

Having explained the significance of the position of the earth in the Aristotelian system, we would like to contrast the image of the earthly and imperfect gathered around the center with the common traditional image of the supreme, incorporeal principle as a point and center of a circle, and the world of manifestation as the periphery or circumference of that circle. In this latter image, the essence is concentrated at the center, and all points in the circle outside of the center are dependent upon it for their existence. It may seem as though these two images contradict each other, but in reality they complement and illuminate each other. In so far as they have metaphysical significance, they are not complete descriptions, for the absolute and its relationship with manifestation cannot be completely described or defined. Both are true in that they both illustrate correctly an aspect of this relationship. All manifested things are projected from the supreme, but at the same time they are surrounded and governed by the supreme. The apparent difficulty of reconciling these two images serves two important functions: first, it suggests the true complexity of the situation, and second, it prevents one from becoming too attached to the mere form of either image, emphasizing that the form of any metaphysical explanation must not be mistaken for its formless meaning.

At this point the apologists for modernity might cede the point that geocentric models perhaps do not represent any hubris concerning the importance of man in the overall scheme of the universe, but that this is really a question of minor importance, since the modern theories still describe the universe more accurately.

That depends entirely on one’s goal in describing the universe. The goal of moderns is to gain mastery over the material world, while the goal of traditional civilizations is to transcend the physical universe. Modern descriptions of the universe help to achieve the modern goal, and traditional descriptions help to achieve the traditional goal. Let us even assume that the modern theory that the entire universe is qualitatively the same is correct. Since the modern theory is examining only the material universe, it does not inquire into the eternal principles and how their influence enters into the material universe, and cannot be said to replace previous models that do not attempt to describe the same thing. Aristotle’s geocentric model, like all traditional models of the universe, is more metaphysical than physical. Other traditional models may differ from the Aristotelian in major ways, but they too are principally metaphysical expressions, attempting to give a glimpse of the ineffable truth through varying means. These models see the material world as a partial reflection of the supreme which, when properly viewed, can bring one closer to it. The modern goal of mastering the material world, even, or perhaps especially when it is achieved, has the opposite effect. Those who are focused on this goal are made blind to the possibility of transcendence.

¹We provide an example of this from the book “Cosmology†by modern astronomer Edward Harrison: “No matter how powerful and remote they became, the mythic gods continued to serve and protect human beings, and men and women everywhere remained secure and of central importance in an anthropomorphic universe. The universe was assembled about a center and human beings were located prominently at the center.â€

The Essence of Organic Society

Alleged critics of modern civilization speak about the superiority of “organic” communities over the “artificial” communities that predominate today, but often they do not understand the very meaning of the words, and only create further confusion. A clear understanding of these terms is essential to any legitimate resistance to modernity. When the most basic terms used to describe the current situation and the possible atlernatives are misunderstood, the best of motives and accompanying efforts can be diverted away from the goal, and even end up serving the enemy.

First we must explain what we mean when we use the word “organic.” By organic, we mean that the different aspects of a traditional society (including farming and hunting techniques, rules of courtship and marriage, house building, clothing and ornament manufacture, myths and legends, music, and a thousand other things) are not the products of one man or even one generation, but rather the products of countless generations. These traditions were given to men by the divine and persisted through many years. They were designed to fit a specific people in a specific environment, and removed from themselves conflicting elements. Over the course of generations these traditions shaped the people, and this cohesive set of traditions made up the entire social environment of an individualk, from cradle to grave. The contrast between this and the modern lifestyle is jarring. In a traditional society, a man or woman dresses in a certain way because that is their way. They wear the clothing produced by their own craftsmen, who make clothing in the way that is in accordance with tradition. Likewise they sing and dance in a way that is in accordance with tradition, and because they draw from tradition, nothing about the way they dress or the way they sing will conflict with any other aspect of their culture.

Let us now turn to what we mean by an “artificial” way of life. Moderns have a wildly strong and irrational attraction to novelty, and this causes them to desire an endless succession of styles in clothing and music, differing styles that have no inner coherence or clear connection to the culture as a whole, and cannot serve as a connection with the divine. Another strong tendency of moderns is the desire for efficiency/profit. These two desires, for novelty and efficiency, overwhelm whatever remnant of fidelity to tradition that might still exist, and often stimulate and enable each other, as the “new” and “improved” almost always go together in the modern worldview. During the rise of modernity, people either failed to recognize or willfully ignored the importance of traditional ways of life. Despite the fact that, for example, the women in their villages had spun wool into yarn for centuries, they decided to manufacture wool in factories because it was more profitable. Despite the fact that their ancestors had sung and danced in the same way for as long as anyone could remember, they embraced new dances because they were novel and “more fun.” In the modern worldview, “more fun”=”better”, when it is more likely that “more fun”=”appeals more directly to the baser instincts”. When these desires for novelty and efficiency gain control, a very significant change occurs. Previously, the dances, songs, clothing styles, diets, family structures, beliefs, farming techniques, etc, that existed together in one place had existed together in that same place for countless generations, had in fact grown up together, and were the way they were because they had developed under similar conditions with similar goals. But now all of the different aspects of society, including manufacturing, entertainment, recreation, etc., are all drawn from different unrelated sources, and, because they are not designed to work with each other, they cannot create a stable environment. It is like trying to build consensus among a group of people drawn from a thousand different countries, each speaking a different language and having different values and beliefs. Perhaps the most shocking is how infrequently anyone has the commonsense revelation that making major changes in every aspect of a society in a single generation might lead to trouble.

Because many people who feel an aversion to the current situation do not understand these terms, they often make proposals to fight modernity that would merely replace one artificial environment for another. One example of this is the belief that if we were to abandon modern industrial society tomorrow, we would naturally revert to the state in which we lived prior to the advent of industry. This belief is based on the assumptions that a) traditional societies were “simple”, and b) that any aspect of human culture can be created by one gifted individual or group of individuals. They reason that if modern ingenuity has allowed us to travel to the moon, surely it can also reproduce the practices and techniques of “primitive” men. This view, however, does not take into account the fact that modern technology is artificial, whereas traditional society is organic. Leaving modern society and living in the woods does not necessarily recreate an organic, pre-modern way of life. To borrow an image from René Guénon, traditional society is organic, and can be represented as a plant growing from a seed, the seed containing in potential form every aspect of the plant, adapting itself as it meets different exterior conditions. On the other hand, modern society is created from the outside by artificially welding together incompatible pieces. This artificial welding together can also represent the modern mind, as it is composed in a similar manner. Throwing this mind into the woods and giving it the task of surviving without invention a, b, and c will not lead to a traditional way of life.

Another example of the confusion that arrises from not properly understanding the terms in question is the phenomenon of the artificial “organic” communities set up by misguided leftists (collective farms, etc). We say that these enterprises are artificial, against the most strenuous claims of those involved, to highlight the point that they do not understand what it means to have an organic community. All truly organic communities have three key components: family, religion, and ethnicity. And this is an empirical claim, not a theoretical one. There are no organic communies that are not shaped and sustained by these three components; and yet modern ideologues claim that family, religion, and ethnicity are three unnatural institutions that ought to be destroyed. These pseudo organic societies in fact rely on the very modern idea that a community is composed of individuals who share a purely rational and conscious agreement or contract.

These proposals are dangerous because they form a false opposition. As the horrors of modernity continue to manifest themselves, more people will become aware of the problem, although most will not be able to accurately describe the problem. In their ignorance they will come accross some charlatans claiming to have an “organic” alternative, and they will think that they have found a way to fight the horrors that they have encountered, when in reality they will be contributing to them, being just as confused and modern in thought as their supposed enemies. The only successful way to fight against the modern world is to build communities using traditional materials as our guide. As westerners we look at natives of “underdeveloped” nations and laugh contemptuously at their traditional customs, failing to realize that even the most degenerate tradition is superior to our modernity, which is a satanic anti-tradition without any vestige of truth or connection with divinity. It is imperative to study and understand the “folk cultures” of our respective nations, as it was these collections of techniques and knowledge that formed a bulwark against chaos and cultural disintegration from time immemorial up until relatively recently, and it is these, together with proper metaphysical understanding, that are the key to living once again in a healthy civilization.

The Problem of Technology

The role of technology in human civilization, especially from the industrial revolution onwards, has been widely criticized for various reasons. Much of this criticism has focused on environmental destruction and the propagation of unhealthy lifestyles. This criticism is certainly valid, but we also must state more specifically the problem of technology from the traditionalist perspective. The main problem of industrial civilization is that the lifestyles and activities necessary to survive and thrive in this civilization are adverse to gaining spiritual transcendence. From this viewpoint the health of the ecosystem is an epiphenomenon, but it is no surprise that when men live with proper reverence for the divine and order their activities accordingly, this results in a healthy environment. In traditional civilizations all activities are carried out with reference to divine contact, and the style of these activities is designed to facilitate this contact. Thus in a traditional civilization the activities necessary for survival and social/political success are also religious activities of the highest order. In industrial civilization the external environment no longer serves as a support for spiritual progress, and in fact is often a hindrance. The following are some specific examples.

In the traditional world combat is a personal contest between warriors. Opponents are faced head on without fear of death. This is true not only of ordinary soldiers, but also of nobles and kings. Personal one-on-one combat in close quarters is preferred because this is the greatest test of a man’s courage and ability, and hence it is success in this type of combat that grants the warrior the greatest glory, that is, the type of glory that is most favored by the gods. Using a bow and arrow is for cowards, and hiding behind fellow soldiers or not venturing forward alone because of the risks involved would be condemned. It is through this sort of combat that warriors gain entry after death to the Isle of the Blessed/Valhalla. Of course, this type of combat is only possible in situations with low levels of technology. An army that attempts to use a traditional fighting style against an enemy willing to use modern techniques and technology would be slaughtered. Courage is certainly required in modern warfare, but the emphasis is on physical organization, not the spiritual qualities of the individuals. Soldiers are valued in so far as they can effectively carry out their role in a machine-like organization. As soon as modern methods are adopted by one side, all others must either adopt similar methods or perish. The choice is between conducting warfare in a way that will serve as a support for spiritual development and conducting warfare in a way that will ensure the survival of the body.

Another example of the divergence between traditional and industrial civilization is the nature of wealth and authority. In traditional societies wealth and authority are concentrated in the hands of an aristocracy, and the main form of wealth is land ownership (or ownership of other resources). This wealth is hereditary, and this is especially significant because in traditional civilizations heredity is principally a spiritual designation. Families maintain ancestor cults and individuals are seen as members of a continuum who hold for a short time what is the property of the entire family, living and dead. After death a member of the family joins the ancestors and is worshiped by his descendants as part of the cult that he maintained while alive. Thus earthly wealth is subordinated in the minds of men to a divine source. Correct management of property is an act of reverence for one’s ancestors and a blessing to one’s descendants. Authority in the community is given to those who have successfully managed their households for generations. This sort of generational success is achieved through an understanding of sustainability and a sense of duty.

This situation, however, becomes impossible with the introduction of other types of wealth, specifically money. Money is a more liquid form of wealth, and can be transferred much more easily. It is abstract, in the sense that it can be abstracted from the things of real value, and hence more easily manipulated and separated from the overall structure of the environment. In general, landed wealth can only pass into the hands of a man who has been groomed by his ancestry and upbringing to manage it. Money can easily pass into the hands of someone with a keen ability to exploit one particular situation in a particular way. Having obtained this wealth with a clear understanding of only a very limited precinct of human existence, this moneyed individual soon attempts to use his wealth to impose his will on areas in which he has no experience, often with a mind to favor exclusively the conditions of his specific money-making enterprise. This situation is exacerbated by the increasing prominence of manufacturing and trade, which depend on money for their operation and in turn increase its power. Indeed money is necessary for the creation of industrial society. For centuries, even millennia after the introduction of money, landed wealth was still felt to be more noble, but elites could not help but accept the new means of gaining and managing wealth, as those who failed to do so would quickly loose their position. Eventually money completely took over, and all landed property was given a monetary value and turned into just another easily transferable asset. The goal in the modern system is to manage a capricious abstraction that takes its existence from man’s imagination, rather than to manage a divinely granted estate, the proper management of which calls forth all of the highest virtues.

These changes, the steady degeneration from the Golden Age, in which men lived without any technology in harmony with the gods and the earth, down to the present era, represent changes in the cosmic environment. As men are forced to adopt industrial civilization, their world undergoes transformation. Every activity in their lives draws them farther and farther away from the truth and transcendence. Men always know hunger, and in traditional civilization the activities that men use to satisfy their hunger, as they are oriented towards the gods, are all means of maintaining divine contact; but in modern civilization the activities that men use to satisfy their hunger are performed with a mind only to the physical results, and thus the desire for food becomes one more force driving men away from the light. It should therefore not be surprising that technology today does in fact resemble black magic. It is a force that grants physical desires (both healthy and unhealthy), but at a very high price. The gifts of technology fulfill earthly desires, desires that can only be temporarily sated, and whose fulfillment is absolutely meaningless upon the death of the individual; but pursuing these desires using modern technology distracts the individual from transcendence, from transcending the dualities of desire and fulfillment and of life and death.

Having assessed the situation, we’d like to add some brief thoughts on where this leaves us. What kind of relationship should we, as traditionalists, have with technology and industrial civilization? If our goal is to spread the truth and re-establish a society based on true principles, then we do not necessarily have to refuse to use modern technology. But when using modern technology in our struggle (by maintaining websites, for example), we must keep in mind that it is a necessary evil forced upon us by the circumstances, and it must always be subordinated to the higher goal. It is also important to realize that a traditional way of life cannot be defined negatively, i.e., by saying that it is what industrial civilization is not, for it is possible to live a primitive existence without technology but also without a traditional understanding of the world. Thus simply abandoning industrial society will not result in an automatic return to tradition.

Consider it this way. According to the Christian tradition, since the fall of Adam, man has been a sinner. Sin is an evil affliction, but also a necessary part of man’s earthly existence. Traditionalists feeling despair because of industrial civilization would be like Christians feeling despair because Adam ever sinned in the first place. These tragedies are part of a larger divine plan, and despair in both cases is not particularly helpful. Furthermore, even a man who has accepted Christ and seeks to spread His word to others is not free from sin. This man still sins as he carries out his work, because there is no other way for men to live on earth. It is not possible for Christians to find salvation by simply ceasing to sin. To find salvation they must discover a transcendent faith in Christ. That is, just abstaining from evil is not enough. Similarly, the struggle against industrial civilization must go beyond decisions about the physical management of the environment.

And finally, perhaps the most crucial point. The true danger of industrial civilization is that man’s life becomes filled with activities and goals that distract him from metaphysical awareness. But this does not mean that metaphysical awareness and transcendence are impossible for men living in modern civilization. After all, there is one source of all things, and circumstances are only seen to be positive or negative from a contingent viewpoint. All things operate according to principles set down by the supreme, and examining any aspect or phase of reality from the viewpoint of the eternal can provide sustenance for clear contemplation. We may no longer be able to test our worth on the field of battle in individual combat, but there is nothing that can be gained by doing so that cannot be gained by us through faith and inner effort. We must realize that the material world is no longer sufficiently integrated with the divine that our spiritual progress can be externalized to such a degree, and that we must not become attached to the mere outer forms of traditional civilization. Regarding this second point, we mean that we must not value any particular aspect of traditional civilization apart from its relationship with the divine (an example of this could be valuing in an emotional and sentimental way forms of combat in the ancient world, and despairing because those sentimental desires cannot be satisfied in the current circumstances). Yet at the same time we must not underestimate the effects of modern civilization on our own minds, even though we have made a modest start on the path towards truth. In traditional civilizations every activity from childhood onwards reinforces spiritual health, as if living one’s entire life in a monastery. In contrast we have been surrounded our entire lives with lies and encouraged to behave blasphemously. Over the years these transgressions and negative influences have created a tangled mess that permeates our thoughts and actions. Spawned by the degenerate world around us, these accretions cannot be ignored. We must view them as we view the rest of our modern environment: at first as objects of disgust and dismay, and later, after a higher perspective has been reached, simply as fellow members of the infinite possibilities radiated from the supreme.

Contemplating the Gods

One of the most difficult concepts for moderns when examining traditional religions is presence of multiple deities. Traditional myths are often used by modernists to argue against “primitive†traditional doctrines. However, these difficulties can be resolved, and the contemplation of the gods of traditional religions can have enormous rewards, and can be incredibly helpful in reaching a metaphysical understanding of reality.

One such myth includes the Hindu doctrine of the Trimurti. The Trimurti includes the three gods Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva, each of which has a distinct function. Brahma is the creator, Vishnu the preserver, and Shiva the destroyer. Each one of these principles is absolutely necessary to explain the world in which we live. That there is creation is evident because there are created things. That there is destruction is evident because things that once existed have ceased to. That there is preservation is evident because there is a point where a thing can be said to be what it is; if only creation or only destruction existed, there would be no stability whatsoever.

A keen reader will already understand that while these three principles (creation, preservation, and destruction) can be separated conceptually, in the material world they always appear mixed. For example, a house is built, a house exists, and a house becomes dilapidated over time; but during the period of building the materials used are already undergoing their own process of decay. Once the house has been built it is always suffering some degree of destruction. And even during the final period of its destruction, for example while suffering deliberate demolition, its component parts persist. In the world of becoming no principle is ever manifested in a pure way, that is, not mixed with other principles, although at one time or place one principle can be dominant over others. Further, the dominant principle can appear to change when one changes perspective. For example, when an organism is in the early stages of its development, when the principle of creation is dominant, it is possible that a particular organ within that organism can perform a function that by itself is dominated by the destructive principle but that still contributes to the overall creative activity of the whole organism. By the same token, during old age, when the dominant principle in an organism is destruction, individual organs can carry out activities dominated by the creative principle. This idea of changing perspectives also applies to the entire cosmic situation. We now live in the Kali Yuga, the end of a cycle of manifestation when the destructive principle reigns and dictates the overall direction, but the principles of creation and preservation are still present to some degree in all manifested things.

So far these three principles have been examined only as they are visible in the material world, but the control that these three gods exert over this world is a symbol for metaphysical ideas. All creation comes from Brahma, all preservation from Vishnu, and all destruction from Shiva, and each of these gods possesses infinite power with respect to their particular attribute. The power of Brahma to bring creation to any fit recipient is never wanting. And further, as these gods exist outside of time, they are not subject to their own attributes. That is, Brahma causes creation but remains uncreated, as creation is a process of change that exists in time. In the same way, Shiva causes destruction but is not destroyed himself, as destruction is also a process of change that exists in time. And Vishnu, the source of preservation, is not himself preserved, because preservation implies the possibility of change, which Vishnu is not even potentially subject to. To further illustrate this last point, the gods, being above time and change, do not move, but that does not mean that they are at rest in the way that a man can be at rest, because the way a man can be at rest is understood by the motion/rest duality that only applies to the material world. In the changeless realm above the material world, these “actions†of the three gods in question are not physical differentiations, but conceptual differentiations. They are among the first differentiations to emerge from the ineffable supreme, and they describe this very emergence (creation), the fact that they have an existence and definition contingently separate from the supreme (preservation), and the fact that from the highest perspective this emergence is an illusion and they will again be returned to the ultimate (destruction). It must be stressed again that at this level (i.e., the contemplation of the gods in their pure state, not as operating in the material world) these “actions†of the gods are conceptual, not temporal. The births of the gods occur outside of time and space, and we can only approximate this truth by saying that they occur everywhere and nowhere, always and never. This eternal and simultaneous conceptual division of the gods is mirrored in the material world by physical creation, preservation, and destruction in time. We trust that thus far the discussion of these three Hindu gods undermines the theory that traditions with multiple divinities represent a primitive stage of human knowledge. The worship of the gods is a way to understand that the material world of change is a limited expression of infinite and eternal powers.

As is often the case, the Hindu tradition provides the clearest presentation of metaphysical ideas, and that is why we began the discussion with an examination of the Trimurti. However, the same general principles hold true for other traditions as well. For example, one aspect of the power of creation can be seen in the worship of fertility gods. I say one aspect of the creative power because fertility gods, such as the Greek Demeter, are responsible for certain creative processes, such as crop production, but not all creative processes. This brings up a very important point. In traditional metaphysics, there is ultimately one source of all things, one principle without which no power or existence could be, although the principle itself is beyond existence and all attributes, including the attribute of power, as this would suggest acting on something other than itself, and thus constitute a duality. As one descends from this ultimate perspective, one sees the first power, the first definable attribute which possess the greatest degree of universality possible for any qualified thing. From this one power all other powers are derived, and this process of delegation and spreading out into multitude can produce many different orders of gods with varying powers and attributes. Different traditions offer different divine hierarchies, but each one, as long as it maintains proper links from the supreme principle down through the different orders, is correct. Thus the confusion, that may accompany a comparison of gods from different traditions when examining the gods only with reference to themselves, vanishes when examining the gods as they exist as a way of describing the ineffable. This supreme principle, of which nothing is a part because it is pure and without parts, and of which nothing is outside because nothing can have an existence independent of it, is described in different ways by different traditions because there is no one way to fully define it, as a full definition would limit that which is unlimited.

Keeping in mind what has been said about the orders of gods as partial representations of the supreme, or perhaps as symbols pointing to the supreme, it is necessary to examine the nature of the stories told about the gods in different traditions, or myths. These myths can be seen as verbal equivalents of statues produced by traditional civilizations. Consider a statue of Apollo produced in ancient Greece: in what way is this statue an accurate representation of the god? A well executed statue can be said to produce as accurate a representation of the god as is possible given the circumstances. Carved out of stone and thus existing in the physical world, it is inconceivable that the statue could fully represent the god, as the god is infinite in power and incorporeal. But the statue can be a symbol that points to the true nature of the god. The authentic statue of a god possesses its authenticity because it is the recipient of the god’s power. To quote Plotinus:

“I think, therefore, that those ancient sages, who sought to secure the presence of divine beings by the erection of shrines and statues, showed insight into the nature of the All; they perceived that, though this Soul is everywhere tractable, its presence will be secured all the more readily when an appropriate receptacle is elaborated, a place especially capable of receiving some portion or phase of it, something reproducing it, or representing it and serving like a mirror to catch a glimpse of it.â€

The god himself may be incorporeal and without physical image, but he possesses in his infinite power every possible authentic image of himself in potential form. The true meaning of the myths is quite similar. The myths do not describe the full power of a god, which is infinite, but rather the way that that power interacts with and shapes particular conditions. A god possesses in potential form every authentic description of the behavior of the god in a particular set of conditions, and every authentic description can increase a man’s understanding of the god. Rather than being able to understand these stories and images by themselves, as could the men who first received them, we are required to supplement our understanding with abstract language. This approach renders meaningless questions like “are the myths true?†or “are the gods real?†The events described in the myths may never have occurred in the material world, may never have entered into the realm of time, but they exist eternally in the god’s essence. Myth is a temporal representation of what does not have beginning or end, just as traditional sculpture is a spatial representation of what does not have dimension.

There is one more point to emphasize on this subject. It is possible for a modern to find pleasure when surveying the elaborate and beautiful flowering of mythic imagery, but then face feelings of despair when told that the gods and their heavenly abodes do not have a corporeal existence, and that they cannot be perceived by any of the senses. It almost feels as though something has been lost. This feeling of loss signifies great ignorance and extreme attachment to the material world, for the gods may not possess physical appearance, but they do possess all the beauty of every single physical representation of them in their infinite power.

Thus there is a chain of symbolism leading up through the different levels of reality. The myths and artistic representations of the gods are symbols of, and point to the gods themselves. The gods are symbols of, and point to the one power that governs all. This one power is a symbol of, and points to the unmanifested supreme beyond power and description. In traditional civilizations all human activities and natural occurrences are linked to the gods and subordinate incorporeal beings. This worldview is an acknowledgment of the progression of reality through increasingly qualified states, and is vertically oriented. The modern worldview is horizontally oriented, in that it seeks for causes only in the material world, and consequently only pursues goals that are on the same level. Nearly all modern activities are aimed solely at shaping the material world in a way that is perceived to be advantageous. In traditional civilizations nearly all activities are aimed at creating or strengthening bonds with entities or forces on higher levels of reality. In such civilizations life is organized around festivals devoted to different gods, and also times that are particularly auspicious for receiving the blessings of a particular god. Sacrifices are made of first fruits, acknowledging that while men may have toiled for their crops, the ultimate cause of their growth is something outside of the physical. Songs are sung because a god might find them pleasant and join with the company of singers. The material world is given little value when compared with the divine when it is understood that all things in the material world depend on the divine for their existence. However, this view does not lead to the oft-maligned doctrine of irresolvable spirit-body duality, for it is further realized that the divine possesses the full possibility of the material world in its power, and that the manifested world is in fact just one possibility contained in that power, only separated from full union with all other possibilities by an illusion.

In traditional societies the relationship with the gods governs a wide spectrum of activities, including many that can be seen as exterior or physical, such as plowing a field, fighting a battle, etc. Some might point out that such connections are impossible in the current situation, and while there is some truth to this, we must not forget that pure contemplation is the highest form of connection with the gods, and it is this sort of connection that we must work for. The great traditions of the world have left us with a wealth of doctrines concerning the nature of the gods, and these doctrines represent the highest objects of contemplation, as they are transcended in contemplation only when the duality of object and subject has itself been transcended, that is, when the highest stage of spiritual advancement has been attained.

The End of a Cycle

Traditional doctrines tell us that the world moves through cycles, each cycle beginning with a pristine state. At this point the world is as close as possible to the supreme principle given the conditions of its manifestation. This is the Golden Age of myth, when men were free from wrongdoing and want, and had regular contact with the gods. We are now near the end of a cycle, in the age known in Hinduism as the Kali Yuga. This age is marked by a satanic inversion of values and general chaos and deformity. Once the cycle has reached its lowest point there is a grand reversion. Paradise is regained, and a new Golden Age is born. In the new cycle there is a new humanity, once again in direct contact with the divine. The end of a cycle should be seen as Armageddon, as the end of a world.

But how should this end, this new beginning, be seen? It is wrong to think that gods will take on material bodies and walk about our world, destroying the wicked and blessing the righteous. Nor should we necessarily expect a literal destruction of the earth and end of time.

Regarding the first point, the gods, or metaphysical powers that govern our world, exist apart from it. They operate without passion or contamination, eternally unchanging. When, in ancient times, they were said to become visible, it was not the gods who descended into the material world, but the human viewers who raised their awareness above the material world. Since the gods are without place or extension, they are potentially available to all things; individuals receive the influence of the gods in different degrees only because of their own limiting conditions. And so it is at the end of a cycle: the righteous are those who cut away all bonds and see the world through the eyes of the supreme, as undifferentiated from themselves.

Regarding the second point, the literal end of the world, one must keep in mind that there is no end of time in time. That is, nothing can enter into time and subsequently bring an end to it. And as all material things are necessarily in time, it follows that no material thing or process can bring time to an end. Time cannot be ended with respect to itself, for if its end is defined as that which comes after time, then its end is defined as something that succeeds another thing, and this definition presupposes the existence of time, for it is only in time that one thing succeeds another. Hence the end of time would be in time, and in reality could never be.

This point can be further clarified by using the imagery of horizontal and vertical orientation. Time is an indefinite horizontal expanse, containing the fullness of time-bound entities. Above this expanse is the unchanging incorporeal world. The end of a cycle is not an acting of one thing in the expanse of time on another, but the reversion of things in time to their supra-temporal source. This reversion is a realization of the contingent and illusory nature of all dualistic conceptions. Time is a reflection of eternity, but the mirror and the original object are one and the same. At the end of a cycle material objects are not destroyed with respect to their material nature, for a particular material body being disintegrated or transformed into another material body does not constitute any sort of transcendence. The new humanity sees all material things as they really are, as contained simultaneously in the infinite power of the supreme, and in this way material things could be said to be “destroyed,†except that this very state (that is, being contained in the supreme) has never actually ceased.

One of the clearest explanations of this new Golden Age comes from the Platonic tradition. In Platonic metaphysics, reality is divided into the world of Intellect, and world of Soul, and the world of matter. Pure Intellect is eternal and unchanging. It is the source of all things and possesses all things in potential, or archetypal, form in its infinite power. All individual ideas exist in the pure Intellect, but this Intellect is still a unity. It is unchanging because it knows itself, and hence all things, simultaneously. Souls are also eternal, but they do experience change. They animate the material world, and undergo periods of degeneration and purification. Material objects are both changing and of limited duration. They receive forms, the ideas contained in the Intellect, but hold them for a limited time before chaos reasserts itself and form is lost. The Platonists identify the Golden Age with the realm of Intellect, and hence the goal of their philosophy is a return to the Golden Age, for they advocate withdrawing the soul from the material world and lodging it in the pure Intellect. Here the philosophers see temporal things from the viewpoint of eternity, just as normal men conceive the eternal in terms of temporal duration.

This should shed some light on the advent of the prophesied new Golden Age. After the final destruction of the old, the new humanity will be a race of philosophers (or of sages, or heroes, whichever term is preferable), full of wisdom and justice, for whom each thing in the world is a symbol pointing to the supreme. It will be noted that when identified with pure Intellect the Golden Age is outside of temporal manifestation, and hence that it is nonsensical to talk about its duration. Rather it is a matter of how long human beings can maintain effective contact with the timeless, and it is more accurate to speak of the return to the Golden Age than of the return of the Golden Age. However, it must also be acknowledged that although the return to the pristine state is a spiritual, not a material process, physical destruction of very great magnitude in our natural and artificial environment may very well occur in conjunction with the spiritual reversion.

And finally, although humanity as a whole may be forced by the conditions of the Kali Yuga into spiritual degeneracy, those very few willing to cut away everything can gain the Golden Age at any time.