The Powerless Of The Power

Vaclav Havel wrote his influential essay “The Power of the Powerless” to describe why people follow along with soft totalitarian regimes. This essay attempts to understand why people create soft totalitarian regimes.

Havel pitches his thesis with an everyday example:

THE MANAGER of a fruit-and-vegetable shop places in his window, among the onions and carrots, the slogan: “Workers of the world, unite!” Why does he do it? What is he trying to communicate to the world? Is he genuinely enthusiastic about the idea of unity among the workers of the world? Is his enthusiasm so great that he feels an irrepressible impulse to acquaint the public with his ideals? Has he really given more than a moment’s thought to how such a unification might occur and what it would mean?

I think it can safely be assumed that the overwhelming majority of shopkeepers never think about the slogans they put in their windows, nor do they use them to express their real opinions. That poster was delivered to our greengrocer from the enterprise headquarters along with the onions and carrots. He put them all into the window simply because it has been done that way for years, because everyone does it, and because that is the way it has to be. If he were to refuse, there could be trouble. He could be reproached for not having the proper decoration in his window; someone might even accuse him of disloyalty. He does it because these things must be done if one is to get along in life. It is one of the thousands of details that guarantee him a relatively tranquil life “in harmony with society,” as they say.

Obviously the greengrocer is indifferent to the semantic content of the slogan on exhibit; he does not put the slogan in his window from any personal desire to acquaint the public with the ideal it expresses. This, of course, does not mean that his action has no motive or significance at all, or that the slogan communicates nothing to anyone. The slogan is really a sign, and as such it contains a subliminal but very definite message. Verbally, it might be expressed this way: “I, the greengrocer XY, live here and I know what I must do. I behave in the manner expected of me. I can be depended upon and am beyond reproach. I am obedient and therefore I have the right to be left in peace.” This message, of course, has an addressee: it is directed above, to the greengrocer’s superior, and at the same time it is a shield that protects the greengrocer from potential informers. The slogan’s real meaning, therefore, is rooted firmly in the greengrocer’s existence. It reflects his vital interests. But what are those vital interests?

Let us take note: if the greengrocer had been instructed to display the slogan “I am afraid and therefore unquestioningly obedient,†he would not be nearly as indifferent to its semantics, even though the statement would reflect the truth. The greengrocer would be embarrassed and ashamed to put such an unequivocal statement of his own degradation in the shop window, and quite naturally so, for he is a human being and thus has a sense of his own dignity. To overcome this complication, his expression of loyalty must take the form of a sign which, at least on its textual surface, indicates a level of disinterested conviction. It must allow the greengrocer to say, “What’s wrong with the workers of the world uniting?” Thus the sign helps the greengrocer to conceal from himself the low foundations of his obedience, at the same time concealing the low foundations of power. It hides them behind the facade of something high. And that something is ideology.

As Plato wrote long ago, cause and effect are different animals, but people frequently confuse effect with the cause of itself (although it is the cause of what comes after it). We see the effect here, which is that normal people make symbolic gestures of everyday obedience in order to avoid ostracism by the regime.

The cause of that situation is the powerless of the power, or the group that forms like a gang, cult or union within a thriving society. Once society establishes itself, it loses its initial purpose, which is to establish itself. At that point, humans become spoiled because they have benefits they could not create for themselves.

The Rise of Ideology

This represents a departure from the state of nature. In the natural setting, small groups have only what they can produce, and those who produce nothing or are unwise tend not to survive. Once civilization is established, its morality takes over from that Darwinian role, and if it fails to weed out the idiotic, the society fails.

The “Powerless of the Power” refers to the group that survives when civilization conquers nature. These people are without actual power, i.e. the ability to do things effectively. But in social groups, they have the power of a gang: they can thwart society. And so, society buys them off, with bribes, welfare and benefits.

Although it seems intelligent and peaceful, that approach backfires because whatever we tolerate, we get more of. Buying off the dysfunctional creates a new layer of dysfunctional people who then need some reason to feel good about themselves and some purpose to which to dedicate to themselves.

Havel explains ideology as the product of the regime, but it is the other way around: the regime is the product of the ideology, because the ideology is personally compulsive to those it ensnares. Ideology explains a not-very-happy life as a process of struggle toward an ultimate good, and thus is the one size-fits-all band-aid for any doubt, low self-confidence, or indecision.

Like most moderns, Havel finds his thinking inverted because he is thinking backward from the present, not from the past to the present. In his view, totalitarianism is the cause because he sees it in the present tense and noticing it causing ideology, which can be explained because causality is a cycle where every cause attempts to re-create the conditions responsible for producing itself, so that it can perpetuate. All things desire power, and this is where Havel misses the cause of totalitarianism — unlike Plato — despite having utterly brilliantly described its mechanism.

As he writes:

Ideology is a specious way of relating to the world. It offers human beings the illusion of an identity, of dignity, and of morality while making it easier for them to part with them. As the repository of something suprapersonal and objective, it enables people to deceive their conscience and conceal their true position and their inglorious modus vivendi, both from the world and from themselves. It is a very pragmatic but, at the same time, an apparently dignified way of legitimizing what is above, below, and on either side. It is directed toward people and toward God. It is a veil behind which human beings can hide their own fallen existence, their trivialization, and their adaptation to the status quo. It is an excuse that everyone can use, from the greengrocer, who conceals his fear of losing his job behind an alleged interest in the unification of the workers of the world, to the highest functionary, whose interest in staying in power can be cloaked in phrases about service to the working class. The primary excusatory function of ideology, therefore, is to provide people, both as victims and pillars of the post-totalitarian system, with the illusion that the system is in harmony with the human order and the order of the universe.

In other words, ideology is a cover story and self-marketing. Whatever is wrong with us, we are made equal by ideology, and then those who wield it well can become more-than-equal.

Pretense And Control

That advantage makes ideology as eternally popular as it is perennially wrong. Healthy, capable people have no need for it; ideology is like explaining why you failed a test or lost a sports game by saying that you did it for the greater good. Ideology excuses failings by demanding that failure become equal to success in the eyes of social judgment, which means that a new decision of failure/success is introduced based on how well one flatters others.

Flattery is telling others what they want to hear. If you want to know the secret of humanity, it is that it is not ruled by secretive groups like the Bilderbergers or Skull And Bones, but by the pretense of the crowd. Each person has some failings or hang-ups, and these are obvious to those around them; the people who reach out to others by explaining those glitches as victimhood will instantly be popular.

This pattern reveals itself at every level of a human group as if we were looking at a high school. The popular kids accept each other despite their basic instability, since they are all attention whores. The nerds group together and forgive each other their weirdnesses and fears.

The fat kids can fit in with the nerds and all the emotionally needy kids cluster in the theater department. In each group, all members forgive others and flatter them with the idea that obvious problems are not problems; this is a defensive outlook created in anticipation of criticism, and it replaces purpose and goal with a perpetual cycle of doubt and denial. The defensive nature of this psychology creates a type of pre-emptive strike, or passive-aggressive projections, called pretense, where those with the most to hide pretend they have the least to hide.

This is the mechanism used to control human groups because it renders them inert by making them focus only on themselves, and in the ensuing state of solipsism, reject the idea of noticing the direction of the group as a whole. That makes it ideal for controllers, who want their subjects to go firmly to sleep so the control forces can use that group as a means to the ends of the controllers.

Human social groups with strong leadership create unselfconscious cultures where people feel that doing right by the group as an organic whole is enough. The person who spies the enemy sneaking in through the woods is not a hero, but someone recognized as a contributor in the group. When that group protects enough people who are not healthy, that group like a cult or gang then seeks to replace the distinction between contributor and non-contributor with a single scale, which is how well one repeats the words and symbols of the ideology that in the absence of purpose is presumed to bond them together.

What results is a conspiracy of flattery. It is impossible to diagnose because it has no center and no leaders, and worse still, none of its members are aware they are doing it. Like a viral infection of the mind, it spreads through the process of socializing between individuals, because when one meets a new person, the choice becomes one of either adopting their mode of behavior or being rejected. Thus it passes along, every person flattering the others in order to form groups, and in so doing, they create a society where there are no permanent things, no guarantee that those who contribute will always be loved. Every day one must keep up the flattery or be excluded. By promising to accept everyone, the conspiracy of flattery has made them slaves to constant threatening social interactions.

These people then rationalize their misery as happiness because to do otherwise is to admit that a great mistake has been made. If they recognize the existential terror and confusion in which they live, the value of ideology as a personal ego-support system fails, and then they will fall out of sync with the rest of the group. Instead, they double down as a way to win the “game” of social success, or at least to have a position where they feel safe.

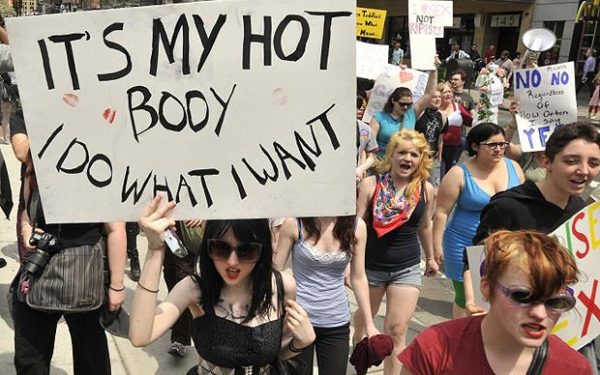

Civilizations die by going crazy. They do so because the powerless, united by ideology, become powerful and divide the group. At that point, the only coherent message is a very simple lowest common denominator one, and ideology — based on what “should” be, usually in the form of universalism or inclusion of everyone whether contributor or not — quickly absorbs the rest of the citizens. Imitating each other in their insanity, they march into the abyss.

Tags: conspiracy of flattery, crowdism, psychology of leftism, vaclav havel