The end game

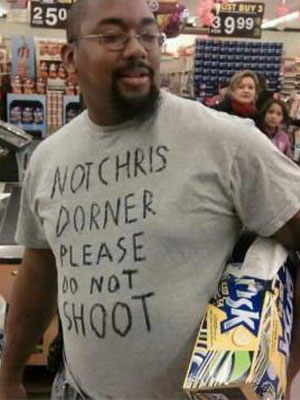

Christopher Dorner made himself useful by demonstrating a pattern of left-wing psychology from which we all can learn. His story was too intriguing for the media to avoid when styled as that of a hard-working altruistic cop unfairly fired for reporting corrupt police who were too rough with helpless innocents being arrested for no reason.

Christopher Dorner made himself useful by demonstrating a pattern of left-wing psychology from which we all can learn. His story was too intriguing for the media to avoid when styled as that of a hard-working altruistic cop unfairly fired for reporting corrupt police who were too rough with helpless innocents being arrested for no reason.

As the story was intended to be told, the loyal crusader for justice risked himself to punish the evil offenders, taking to the streets for the public and heroically dedicating his life to weeding out the wicked ones. Who could oppose the selfless oppressed underdog of this superhero narrative?

But scratch the surface and the phony posturing becomes clear, revealing traits we see in every revolution and call for “rights” to be recognized. Claiming to have suffered perceived prejudice since shortly after birth, Dorner expresses his frustration with society, as if some supernatural force has selected him for random misery and failure. He solely concerns himself with accusations, blame, and excuses rather than constructive plans for personal betterment and success.

In his manifesto, Dorner aligns with leftist politics, while admitting his long depression and deep saturation in entertainment products, though not considering their possible connection and relation to a lifestyle of frustration and outbursts.

One will always encounter struggle, opposition, and difficulties needing to be overcome. How we face these reveals character and yields the results obtained. Marcus Aurelius devised a morning prayer to prepare a positive outlook and bulwark, declaring the most trying expectations and explaning why one must not break under their weight:

Begin each day by telling yourself: Today I shall be meeting with interference, ingratitude, insolence, disloyalty, ill will, and selfishness — all of them due to the offenders’ ignorance of what is good or evil. But for my part I have long perceived the nature of good and its nobility, the nature of evil and its meanness, and also the nature of the culprit himself, who is my brother; therefore none of those things can injure me, for nobody can implicate me in what is degrading. – Marcus Aurelius, Meditations

Traditionalists view problems to dissect their holistic structure, revealing the key broken aspects needing repair. Venting, faulting, and acting out is personally satisfying because it feels like something is being accomplished by lashing out at the world, but this pleasure is a false narrative that attempts to shift the consideration of the problem from its true origin.

The frustrated one dreams of revenge by making others suffer, gaining advantage through a lose-lose proposition that hurts others by making their situation worse. If your situation is already bad, hurting others who are doing well makes you more equal, and thus an underdog’s justice finds moral ground from which to undermine and spoil everything healthy, strong, and sensible.

A culture of revenge consists of an infinite chain of attacks against one’s perceived enemies, with no goal greater than sustaining a string of bitter destruction. The supposed enemies are not real, the supposed slights are insubstantial, and the entire weltanschauung is grossly defective, yet damage is performed because one has conjured this false reason for their misery and just as faulty a plan for its remedy.

Well adjusted people use time tested solutions to set disorder straight. When you instead see crazy explanations and wild crusades proposed in place of solutions, dysfunctional and futile thinking are busy at work.

Dorner vowed warfare against former colleagues, admitting his plan to murder many people. He then explains the purpose of his killing spree was to supposedly “clear his name” and drive out corruption from the police force, as if such killings have ever led to that result, or could be reasonably expected to.

The revolutionary performs actions for his own purposes and then lies about his motivations to cast them in a benevolent light. Actions at odds with claimed purposes is a dead give away of incoherence, and suggests the actual motivations are unknown or unmentionable, often being little more than a personal problem not yet addressed.

As Dorner fled to a cabin for the last battle in his police war, reality had crept in and encircled him. He realized his hero fantasy didn’t hold up, was factually incorrect, and that suicide was an appropriate exit. Being unable to spin the tale further, he cleared himself away just as illegal aliens self-deport when local enforcement is announced.

This cognition from self-reflection should be forced on all advocates of unsustainable practices and politics so they must confront their deranged projections. At that moment, they will have to either find some historical precedent to buttress their propositions or admit being swept away by a nutty fantasy that enticed them because of troubling emotional or personal failings.

Perhaps they will go quietly and walk away from their mistakes or check themselves out, sparing us an expensive tantrum to clean up afterward.