The Choom Gang in the White House

Jonathan Gruber triggered a political tempest when videos surfaced of him admitting, nay, bragging, that he and his comrades not only deceived voters, but manipulated them by using key terms to mislead and then delivered something else entirely.

Whether or not Gruber’s actions are evil, acceptable or merely predictable, he raised an interesting point for the American voters: would you elect yourself to the position of voter? After all, it seems like every year confidence in government falls and yet the voters keep consistently electing bad leaders.

As they say in the hills, fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me. It turns out the Barack Hussein Obama presidency has brought unprecedented levels of corruption, failure and reduced national prestige, but voters seemingly excited about his half-African origins and strong liberal credentials voted him into office twice. Is it time for the voters to step down?

The question of whether voters are to be trusted at all leads us to the fundamental question of whether groups of people can be trusted at all. As individuals, most humans show poor judgment in managing their personal lives; this is why very few people actually have their acts together. In groups, humans behave like every committee meeting any of us have ever sat through, which is aggressive individual drama followed by the usual compromise.

We the people may be not-so-sane. The Obama presidency is the result of Baby Boomers and their effect on politics. It may be that this does not reflect a political opinion so much as the human tendency to vote according to the mental image they have based on past media, trends and social tropes.

For example, Baby Boomers influenced our culture and created The Narrative: the notion of independent rebels, cast out by society, joining together in a kind of second American Revolution to bring tolerance for all. Barack Obama is entirely a creation of this narrative of the Baby Boomer generation:

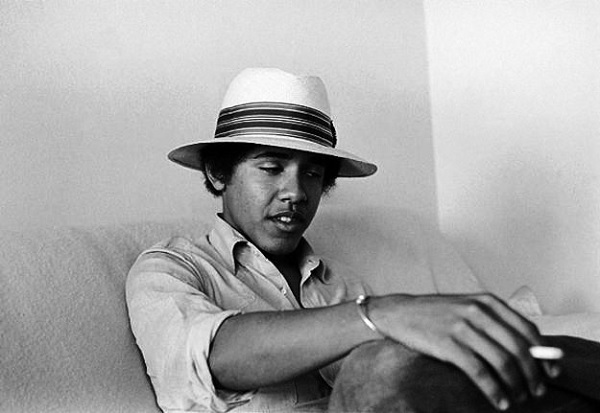

While in high school at the Punahou School in Honolulu, Obama began associating with a group of boys who “loved basketball and good times,” says Maraniss. The group — “decent students and athletes who went on to become successful and productive lawyers, writers, and businessmen” — dubbed itself the Choom Gang. A favorite hangout was a lush hideaway called Pumping Stations, where they parked their cars, turned up Blue Oyster Cult on their stereos, “lit up some ‘sweet-sticky Hawaiian buds,’ and washed it down with ‘green bottle beer.'”

Young Boomers raised on West Side Story (1957) identified with the poor Latino protagonists (who were in gangs with equally awkward names to “the Choom Gang”) and saw themselves as rebels against a stultifying social order. And who were the forces of evil in that universe? Old white guys. That thread of underdog versus oppressor runs through all popular media, even hipster millennial favorite Napoleon Dynamite.

Getting the Big Choomer into the White House helped the Baby Boomers act out that vision of rebellion. Take back the power from those old white guys! Get one of us in there — he was a rebel, smoked weed which signals his hipness to the “tune in, turn on, drop out” generation, and even better, he’s not part of the historical majority — and take over the wheel. Other generations, indoctrinated by Baby Boomer writers and politicians, follow the same knee-jerk response.

When history records their influence, Baby Boomers will be seen as a generation of rebels stranded in perpetual adolescence. They grew up in the Dale Carnegie 1950s when the ideal occupation seemed to be salesman. After a disastrous world war, people cashed in on the remaining industrial economy by selling each other stuff. They created a society worth rebelling against: driven by commerce alone, directionless, and wracked with pretense and an impulse to hide its fetishistic misdeeds and corruption.

Their parents, having fought this war, presented a prime target. These were the children who partied their way through the 1920s and flirted with Communism during the 1930s, then suddenly got “conservative” in self-interest as they aged. This group bore with it the sense of inevitability that came with the first World War, namely a sense that our society had reached its ultimate position in history and there was no other path. Industry had replaced agriculture, science replaced religion, and in that light it only made sense that democracy replaced kings and authoritarians.

During the 1940s, this group experienced the transformative event of total mobilization. To their surprise, they liked it. For the first time, their lives had purpose. But with it came resentment. Rosie the Riveter, late the hero of the aircraft production line, did not want to return to being Martha Barnsley of Deep Hill, OH. As a result, the “Greatest Generation” became the biggest group of addicts to keeping up with the Joneses and other social status activities, horrifying their children.

Their children perhaps justifiably hated them, and did the one thing they could do to shatter the WWII revolution: call their parents pocket Hitlers and demand a movement that supported the Other Side, which in the 1950s and 1960s was the Soviet Union. This was rebellion in its purest form: support the enemies of the tribe, criticize the tribe by its own principles, and demand autonomy from the parents. It was designed to shock, disturb and destroy the world their parents had created.

These youngsters viewed themselves as anti-heroes who would tear down the empire of evil by electing differentness and destroying all that they had known. Iconoclasm became their behavioral pattern; whatever their parents did, they did the opposite. This inversion is characteristic of all rebellions which first labor to prove they are not like whatever power has the authority against which they are rebelling.

Unfortunately, the Baby Boomers kicked off the biggest upheaval in Western society since the Enlightenment. The 1968 revolutions led to a de facto adoption of socialism within the West, even as the end results of socialism could be seen in the Soviet bloc countries. But in contrast to the deskbound world of their parents, it seemed like a new frontier.

As the world watches the Barack Obama presidency wind down like a Choom Ganger feeling his weed and beer wear off amidst the chaos of his life, voices rise in opposition to The Narrative. Could we be leading ourselves in circles, telling ourselves comforting lies and then voting on them, then telling ourselves the same lies to explain the failure? But then other voices shush them and tell them everything is fine, to just go back to sleep and wait for a morning that will never come.

Tags: barack hussein obama, choom gang, liberalism, the narrative, visual politics