Separating God From “God”

Many who identify as Christian actually believe only in God. They need a form for it, a visual imagery, so they adopt Christianity because this is the easiest vessel for their faith. They grew up with churches, hymns, the ten commandments, and Christmas so this is the path of least resistance.

Their actual belief comes from an intuitive gut instinct faith that the world is good, tends toward good, and has its origins and our post-death future in something wonderful. If we had to summarize religion, we might find it in those things entirely, but it expands to implications of those notions:

At the core of the Perennial Philosophy we find four fundamental doctrines.

- The phenomenal world of matter and of individualized consciousness — the world of things and animals and men and even gods — is the manifestation of a Divine Ground within which all partial realities have their being, and apart from which they would be non-existent.

- Human beings are capable not merely of knowing about the Divine Ground by inference; they can also realize its existence by a direct intuition, superior to discursive reasoning. This immediate knowledge unites the knower with that which is known.

- Man possesses a double nature, a phenomenal ego and an eternal Self, which is the inner man, the spirit, the spark of divinity within the soul. It is possible for a man, if he so desires, to identify himself with the spirit and therefore with the Divine Ground, which is of the same or like nature with the spirit.

- Man’s life on earth has only one end and purpose: to identify himself with his eternal Self and so to come to unitive knowledge of the Divine Ground.

These four doctrines constitute the Perennial Philosophy in its minimal and basic form.

In other words, at the core of religion is a belief in divinity and an order beyond the physical, although not necessarily one that operates under different rules as is asserted in dualistic philosophies, and not so much God as a continuum from earthly animal to divine.

Those who are religious will find it hard to separate this eternal religiosity from their specific religion, especially if raised Christian. Abrahamic religions have a common root which came before Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Islam, and Christianity, and it began this process.

In the proto-Semitic faith, symbolic religion replaced idol-based religion. Instead of worshiping the golden calf, you worshiped the symbolic state of union with the golden calf, sort of like having an icon of a golden calf on your phone instead of a tangible idol before which to burn sacrifices.

The symbolic religions of the Abrahamites came in two layers, like the separation between Hinduism and Buddhism. In the first layer, they worshiped the symbol directly through rule-following and a complex theology; in the latter, organized mental state became the goal so that divinity could be achieved.

Expanding on this, the early Semitic religions emphasized worshiping the symbol like the idol: hold it forth, and you may take some of its power, a form of rationalization where you work from the category (symbol) to the specific instance, like deduction from human forms instead of natural events.

When the Christian era dawned, the Buddhist- and Greco-Roman-infused notions that made their way into the faith consisted mostly of the process of casting aside complex rules and instead focusing on orienting the self toward mental calm, self-discipline, and pursuit of the good.

The latter came to us entirely from the Greeks, who emphasized transcendental excellence (arete), an almost undefinable goal of rising above whatever currently exists in quality without changing the natural order. Develop what is real, not attempt to change nature, it urged.

The notion of looking inward, featured heavily in Buddhism and Daoism, corresponds to the Greco-Roman and Nordic pagan notion of intuition and self-discipline. The unruly self contains many truths, but they must be separated from mere impulses, fears, and projections.

Through this transformation, the Semitic religions became fully modern but never lost their symbolic nature. For this reason each of them confuses the symbolic with the literal, which is why they emphasize obedience to a particular God, his magic words, and magic symbols.

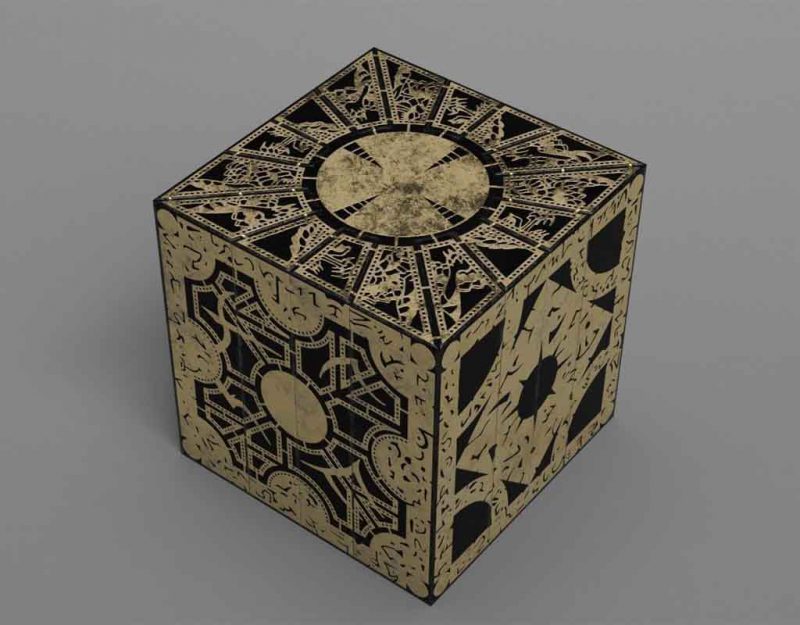

Consider the average horror film. At some point, an individual is possessed or a demon-spawn crawls forth from a gateway to another world (a world which, in dualistic lore, has its own rules independent of those of thermodynamics and nature).

The characters beat it back with a combination of realistic, literal actions like whacking it with a stick and spells, chants, mantras, invocations, and litanies of magic words accompanied by magic symbols drawn on the floor in salt.

In this we see the rationalization inherent to symbolic religions. If it is evil, it must behave according to the rules of our definition of evil, and therefore our symbols, chants, and gods will repulse it.

The perennial vision takes an opposite view. In it, there are no sacred symbols; there is only Reality, including its Divine Ground which enwraps this world like a warm hug, and the ability to manipulate it whether by physical or mental means.

With the symbolic view, you get “God,” or the divine entity which you must worship using the magic words, symbols, and rituals. With the perennial view, you encounter a naturalistic faith where the gods are an offshoot of nature and behave much as nature does.

Christianity did not create the modern era. It faces several challenges — it is commonly interpreted as universalist and dualistic, it confuses the exoteric and esoteric, and it is written down, thus prone to interpretation, as well as unavoidably foreign owing to its middle eastern roots — but came along when a unifier and control mechanism was needed, thus was adopted through a series of brutal religious wars.

Modernity happens to societies as they age, per the civilization cycle that Plato chronicled best. Early societies have a goal and focus on the spirit of arete, but as they grow, waste humans accumulate who are unable to have a goal, thus control is chosen.

Control consists of setting up categories of good and bad based on method, not goal, so that people can be forced to use these methods in uniformity at the same time, creating a mental state of obedience and unity. Control creates a mentality of complacency based on trust that the “system” works.

In control-based societies, the map is the territory, because the symbol determines how people react socially to what you do. It matters less what you do day-by-day than the grand statements and gestures you make, paralleling the symbolic nature of the religions that such times adopt.

The modern time consists of dominance by category. This arises from the confusion of method with goal, which is what happens when you delegate tasks to others, use money to buy products and services, implement standards procedures or tools, and otherwise separate from nature with society as the mediator.

That in turn spurs on an urge to regulate effects as causes. If someone bought a certain product, in this view, we can discern an intent from it and a result it would have caused; if you want unity, call a meeting, and this forces people to come together even if their will is otherwise.

Categorical thinking arises from the adoption of standard methods instead of thinking cause-to-effect, meaning that you start from results and see what options you have of achieving those results. That latter thinking, an ends-over-means calculus, induces social fear.

Control placates social fear. It does so by moving to a means-over-ends approach which says that as long as you were using approved methods in the right context, you did no wrong even if the attempt failed. This removes the fear people have of being brushed aside for not understanding the goal.

The desire for control, or the use of categorical methods to regulate others, arises from individualism, or the idea that the desires of the individual must come first before social order or natural order. That in turn comes from a fatalism that emphasizes fear over hope.

In its analysis of causality, we have cause, effect, results, and conclusion, or what humans think about the event, which is usually made into symbol. That forms the basis of a utilitarian-like philosophy which hopes to exclude all things people fear, replacing them with “safe” methods.

As a society grows, it produces excess people because the efficiencies inherent to civilization mean fewer necessary jobs. These people float around without purpose, and bond in their fear that they will be seen as less worthy for this, so demand exclusion of ends-over-means as a philosophy.

They want conclusions about a method — how safe it is — to stand in place of ends-over-means thinking, in which you first choose a goal and next select a method to fulfill it, which leaves methods that involve fears (those that make others look bad) remain on the menu.

Consequently, they create symbolic religions. Some actions are categorized as bad, no matter for what end you do them; others are categorized as good, even if results are bad. This replaces the pagan ends-over-means “good to the good, bad to the bad” described in Plato.

In this way, method comes to matter more than goals or results. Conclusions and symbols, which control public optics, become more important than achievement. Individuals matter more than order, mores, standards, and values. This is the cornerstone of modernity and starts a decay and death process.

In Abrahamic religions the symbolic categorical system replaces a need for mental order mirroring natural order with a good/bad calculus. This reflects the mixed-race nature of the Semites, who lost any consistent culture and had to invent a rules-based religion as a substitute for it.

The Semitic region, formed at the intersection of Africa, Europe, and Asia, was also famous for its commercial ability, and symbolic religions fit well within commerce. Eliminate bad methods, motivate everyone to do the same thing, and you have order enough to sell stuff.

These religions also revealed the Asiatic origin of much of Semitic thinking. If methods replace goals, and effects replace causes, then obedience matters, and only those who obey are rewarded, establishing an Asiatic-style centralized control system like that of Darius of Persia or Genghis Khan.

In these societies, method becomes effect so that the collective meta-goodwill can be regulated. This bled over into their religions which emphasized good methods versus bad methods and replace goal with rules, later reformed into a mental state of benevolence suitable for commerce by Christianity.

Some might even say that the West adopted Christianity with the rise of the middle class which, lacking the arete-bound inclination of the aristocrats, simply want to be able to sell stuff, have property, and keep minimal social order instead of crusading for mental clarity and goodness.

With this in mind, we can see that the best of our people are deeply religious in a sense that transcends religions. They believe in God, and choose “God” because he is what is on offer in the modern mental landscape.

At their heart however, these people are not Christians, but simply theists or possibly pagans who believe nature as a whole is alive, with multiple gods manifestating its tendencies. Such an attitude is unsuitable for commerce and offends a large number of people who buy stuff.

Tags: christianity, meta-goodwill, religion, symbolic religion