How Leftism Bankrupted You To Pay For Diversity

When people talk about how well America is doing, they inevitably mention the economy, since we have no culture to speak of and our social environment is massively unstable. We can claim modernity is good if we look at wealth, technology, and democracy only.

As we dig deeper, however, we find out that in fact our economy has been stalled for some time, and the middle class is getting savaged. As some sources have noted, pay has been stagnant despite rises in productivity and growth:

From 1973 to 2017, net productivity rose 77.0 percent, while the hourly pay of typical workers essentially stagnated—increasing only 12.4 percent over 44 years (after adjusting for inflation).

This is part of the wage stagnation that we have experienced in the West, starting in the 1960s and accelerating in the 1970s through the present day:

After adjusting for inflation, however, today’s average hourly wage has just about the same purchasing power it did in 1978, following a long slide in the 1980s and early 1990s and bumpy, inconsistent growth since then. In fact, in real terms average hourly earnings peaked more than 45 years ago: The $4.03-an-hour rate recorded in January 1973 had the same purchasing power that $23.68 would today.

Meanwhile, wage gains have gone largely to the highest earners. Since 2000, usual weekly wages have risen 3% (in real terms) among workers in the lowest tenth of the earnings distribution and 4.3% among the lowest quarter. But among people in the top tenth of the distribution, real wages have risen a cumulative 15.7%, to $2,112 a week – nearly five times the usual weekly earnings of the bottom tenth ($426).

Some hypothesize that this is the result of globalism which has caused wages to go down as cheaper competition has become available:

Falling living standards are no accident. The effect of expanding international trade is to gradually equalize wages and working conditions world-wide. The demise of union strength, attributable in part to the emergence of this world market with its billions of low-wage workers, is also in part a result of unions themselves. Union bureaucrats who have helped pursue the im-perialist policies of the U.S. through the American Institute for Free Labor Development (AIFLD) and campaigns for “democratic unions,” have contributed to a process which has already greatly increased “Third World” conditions in U.S. cities.

The reduction of high-wage industrial work in favor of low-wage, part-time service and information work was in response to the equalizing forces of the world market. As capital flows to areas of optimal profitability, living conditions worsen in its wake, creating a two-tiered society that signals misery for the majority. It is a process that cannot be derailed by an “honest” or even “progressive” government enmeshed in the unforgiving world market. Union leaders who campaign for “jobs” are either cynics or genuinely myopic. They know as well as anyone who reads the daily papers that the wave of restructuring that helped produce this “downturn in The Economy” has permanently reduced the number of workers needed.

At the same time wages were stagnating, we saw a massive rise in bureaucratic/administrative jobs which essentially constituted make-work to keep the proles busy:

But rather than allowing a massive reduction of working hours to free the world’s population to pursue their own projects, pleasures, visions, and ideas, we have seen the ballooning of not even so much of the ‘service’ sector as of the administrative sector, up to and including the creation of whole new industries like financial services or telemarketing, or the unprecedented expansion of sectors like corporate law, academic and health administration, human resources, and public relations. And these numbers do not even reflect on all those people whose job is to provide administrative, technical, or security support for these industries, or for that matter the whole host of ancillary industries (dog-washers, all-night pizza delivery) that only exist because everyone else is spending so much of their time working in all the other ones.

While corporations may engage in ruthless downsizing, the layoffs and speed-ups invariably fall on that class of people who are actually making, moving, fixing and maintaining things; through some strange alchemy no one can quite explain, the number of salaried paper-pushers ultimately seems to expand, and more and more employees find themselves, not unlike Soviet workers actually, working 40 or even 50 hour weeks on paper, but effectively working 15 hours just as Keynes predicted, since the rest of their time is spent organizing or attending motivational seminars, updating their facebook profiles or downloading TV box-sets.

In fact, many jobs are entirely irrelevant, and that does not even take into account whether the economic activity in which we are engaged in necessary or not. Much of the red tape and paper pushing work could simply be eliminated:

Something like 37-40% of workers according to surveys say their jobs make no difference. Insofar as there’s anything really radical about the book, it’s not to observe that many people feel that way, but simply to say we should proceed on the assumption that for the most part, people’s self-assessments are largely correct. Their jobs really are just as pointless as they think they are.

If my own research is anything to go by, bullshit jobs concentrate not so much in services as in clerical, administrative, managerial, and supervisory roles. A lot of workers in middle management, PR, human resources, a lot of brand managers, creative vice presidents, financial consultants, compliance workers, feel their jobs are pointless, but also a lot of people in fields like corporate law or telemarketing.

What caused this change? The first culprit blamed is automation or rather, the rise of the digital computer, which started in the late 1960s with the first powerful UNIX machines and eventually downsized to the desktop:

One of the most prominent among the suppliers of minicomputers was Digital Equipment Corporation, otherwise known as DEC. Their PDP line of machines dominated the market, and can be found in the ancestry of many of the things we take for granted today. The first UNIX development in 1969 for instance was performed on a DEC PDP-7.

DEC’s flagship product line of the 1970s was the 16-bit PDP-11 series, launched in 1970 and continuing in production until sometime in the late 1990s. Huge numbers of these machines were sold, and it is likely that nearly all adults reading this have at some time or other encountered one at work even if we are unaware that the supermarket till receipt, invoice, or doctor’s appointment slip in our hand was processed on it.

However, much like blaming globalism, this seems like a partial explanation. After all, while computers took over much of the work, they also opened up new opportunities, but most of those seem to go toward make-work as well.

We have a structural problem, not a technological one. Even with globalism, we could make products here, if the cost were not so high. Even with technology, we still have plenty of actual work to do, but somehow fake jobs have proliferated.

Our answer — like all interesting things — comes from a complex argument. First, we should look at what really changed right before the wage recession hit, and we quickly see two things: taxes and immigration.

In our time, this measurement was complicated by the fact that multiple taxes kicked in during this period at federal, state, local, and regulatory levels:

The 1920s and ’30s saw the creation of multiple taxes. Sales taxes were enacted first in West Virginia in 1921, then in 11 more states in 1933 and 18 more states by 1940. As of 2010, Alaska, Delaware, Montana, New Hampshire, and Oregon are the only states without a sales tax. President Franklin Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act in 1935 and Social Security taxes were first collected in January 1937, although no benefits were paid until January 1940.

These are just a few of the many taxes Americans are subjected to. Others include cigarette and alcohol taxes, energy taxes, aviation taxes, property taxes, telecommunications taxes, and state income taxes. The Tax Foundation calculated that in 2009, Americans on average had to work through April 11 just to earn the amount of money they would pay in taxes over the course of the year, better known as tax freedom day.

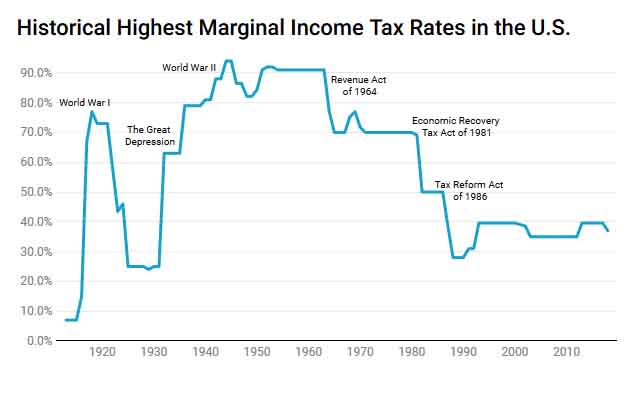

You may notice a peak right before the slowdown, but this chart measures on federal income tax. Other taxes were expanding at that time as well, which meant that the total tax burden increased a great deal more than previously measured.

Naturally, finding a figure for that is impossible, since it varies from city to city, since the total tax burden is an aggregate of federal income tax, gasoline and excise taxes, local property taxes, state sales tax, local sales tax, and regulatory taxes like alcohol, aviation, energy, and utilities. In sum, taxes rose during this time.

What else happened? For starters, our overlords found a way to con the voters into approving a permanent flood of low-cost labor which depressed wages:

The 1965 legislation was named the Hart-Celler Act for its principal sponsors in the Senate and House of Representatives. It abolished the quota system, which critics condemned as a racist contradiction of fundamental American values. By liberalizing the rules for immigration, especially by prioritizing family reunification, it also stimulated rapid growth of immigration numbers. Once immigrants had naturalized, they were able to sponsor relatives in their native lands in an ever-lengthening migratory process called chain migration. That unintended consequence is Hart-Celler’s enduring legacy.

“The 1965 immigration law quickly transformed the ethnic portrait of the United States,” scholars have noted. At first the new immigration came largely from southern Europe, especially Italy. But that stream played out in about a decade. Meanwhile, immigration from Eastern Europe was limited by repressive communist governments.

By 1980, most immigrants were coming from Latin America, Asia, and Africa — in numbers far greater than the annual average of 300,000 that had prevailed during the 1960s. Despite assurances by Hart-Celler advocates that the bill would add little to the immigrant stream, more than seven million newcomers entered the country legally during the 1980s. That trend has continued. Meanwhile, illegal immigration also began a decades-long surge.

Another major factor in the immigration boom was the worldwide population explosion. The population of Latin America, for example, soared from about 200 million in 1960 to 600 million by the end of the century. “As Latin America’s population has grown and its governments and economies have foundered, more and more of its people have looked northward for relief,” journalist James Fallows wrote in 1983.

In other words, we began taking money from the middle class and transferring it, through entitlements, to the new population which surged over the borders in both legal and illegal forms.

On paper, the decisions by our leaders made sense. We needed to stay competitive and keep growing, and we could do that by adding new consumers. Those could be taxed, and the system of entitlements that we created in the 1930s could be sustained.

Unfortunately, those we added others in the 1960s, expanding the social safety net in the type of general anti-poverty program that politicians love but that economists fear. The tax burden took money out of the economy and siphoned it into government and the underclass.

In addition to that, the administrative state — created in 1935 by Supreme Court decision — expanded, writing many regulations and laws which raised the amount of paperwork, compliance, record-keeping, and other non-essential burdens. These expanded in the 1960s.

With women coming into the workforce and a steady flow of unskilled labor, the market pushed the educated and literate into glorified clerk positions as administrators of the managerial bureaucracy, causing bloat in the labor market instead of focus.

Government further enhanced this by making itself huge and taking money out of industry, at which point businesses sought to generate as many deductions as possible, which made it appealing to hire more people in useless roles.

This shows us taking the exact same path as the Soviets — building a large state to redistribute wealth — even if our methods were different, and we kept a capitalist economy at the heart of our system.

In fact, history suggests that most societies go out roughly the same way: humans decide that they can do better than nature, and take care of everyone instead of following the rough command of natural selection to reward “good to the good, and bad to the bad.”

This makes the group feel good. No one feels left out, there are no exceptions, and humanity is in total control of itself. This denies however that the same logic behind nature operates in our societies, and over time, we decrease the good and increase the bad, precipitating the end.

America at the present time has decided to go out with diversity. Transferring wealth, power, and status from its founding population to its new replacement population, it has minimized everything that once made it good, and replaced it with a hungry, formless mob.

If you wonder why your actual purchasing power and wages appear stagnant, look no further than to the changes we brought about in the 1930s and 1960s which enact this tax-and-spend wealth transfer. They will be our epitaph.

Tags: antiwork, bullshit jobs, bureaucracy, management, soviet union