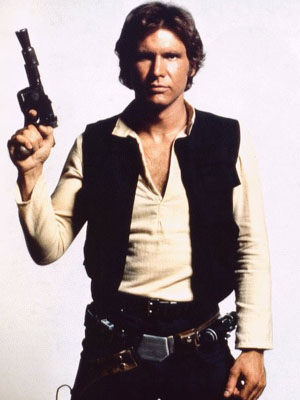

Han Solo

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Star Wars was huge. Not huge in the way that the Iran hostage crisis was huge, but huge in the sense of always being in the background of every conversation.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Star Wars was huge. Not huge in the way that the Iran hostage crisis was huge, but huge in the sense of always being in the background of every conversation.

Looking back on it, it’s clear why: Star Wars was not only great sci-fi, but it explained where we’d come from. The destruction of Alderan, or Hiroshima if you prefer. The jack-booted stormtroopers and individualistic rebels fighting them. The mystical connection between science and a Buddhist/Christian hybrid religion.

At the time, it wasn’t uncommon for people to talk about this film. It was reasonably common for women to discuss it. When they did, many of them would swoon over Han Solo. Who? He was a character who was down on his luck, always late on his payments, and making it hand-to-mouth as a smuggler.

Middle-class American women went nuts for the guy, and it wasn’t just Harrison Ford. The mystique intrigued them. Instead of a boring day-to-day existence of keeping the family together, or of going to work and then doing that, here was this romantic and devil-may-care lifestyle.

They just about melted over this guy. This was the antithesis of the work-husband, who went out there and slugged it out in the cube-farms and offices of America, bringing home the bacon. In comparison to this lovable rogue, the work-husband was drab, boring, even an obligation and source of misery.

Nevermind that not a single one of these women would have accepted a marriage proposal from Han Solo. You’d have to be insane to do so. Intergalactic smugglers don’t have health insurance, car insurance, life insurance or regular money. You’d be living like a slave Leia, locked away in his ship as he dodged bullets.

Like so many popular things, “romantic” is great in theory but horrible in reality. This is because the same thing that makes romantic appealing, which is that it’s irresponsible, also makes it dysfunctional. It’s an illusion through-and-through that any of these women would want to live that way, which is why they love the illusion.

After all, the best illusions are the ones we would never consider as real-life decisions. That way they hover above us, delicious alternatives to our hum-drum (speak for yourself) lives, impossible and thus forever immortal, abstract, clean and smooth, untouched by the daily chaos and obligation.

It’s worth noting that if these women had 18-year-old daughters, and Han Solo showed up in his Millennium Dodge Falcon to haul them off to the Alderan bowling alley for a night of cheap beer and heavy petting, these “romantic” women would very un-romantically be calling security in their gated communities.

They may have been drugged with the dream of a temporary illusion, but these women were not fools. When the water heater breaks, you don’t want Han and Chewie to put it back together with duct tape. You want reliable work-husband to research 400 plumbers and find the right one, or spend half the weekend doing it himself, to his standards.

Wherever we go in life, the distraction divide exists. We know what is practical to do, and yet we dream of the other side. The other way. Some alternative, a different life. And by the nature of needing to dream, we project into it impossibility and an untouchability that guarantees it’s inapplicable to any life we would want to lead.

Political choices are the same way. When people are asked to solve problems, they are conservative. When we start talking about outer-space concepts like morally correct and socially successful, we end up with a consensual reality of things people want to believe are true. What they wish their lives were, not what they must be.

This is the nature of the self, liberated from constant labor by technology and the organization of first world societies (hygiene, laws, police, etc.). Looking for a way to be more powerful, it thinks of what might flatter it and make it feel truly important, which is invariably the dream of the other side and not reality.

When misled by others, it then chooses that option as if it were real. Self-pity is its blank check here. The wealthy white woman from the suburbs must look over her comfortable life and declare it “boring.” The first-world college students must look to the third world as a form of greater truth or excitement in living.

This is part of the consensual reality in which most modern people live, fed by the chatter of their friends, a constant overload of media, and well-intentioned government education. It’s a dream and an illusion, but it feels good, so they walk toward it like sleepwalkers, feeling good about themselves proportionately to their denial of reality.

Whichever society finds a way to survive into the next millennium will do so by smashing the tendency of rampant individualism that provides this orgy of egomania. It will center people on a reverent attitude toward life itself, and evade any mention of dreams that do not involve that world.

Unfortunately for our modern dreaming, this society will not be romantic but Romantic. It will endorse the lawless and chaotic, the heroic and the eternal. What it will not endorse is the raging supremacy of the individual ego that in its zeal for power, creates a utilitarian society of mundane boredom and calls it progress.