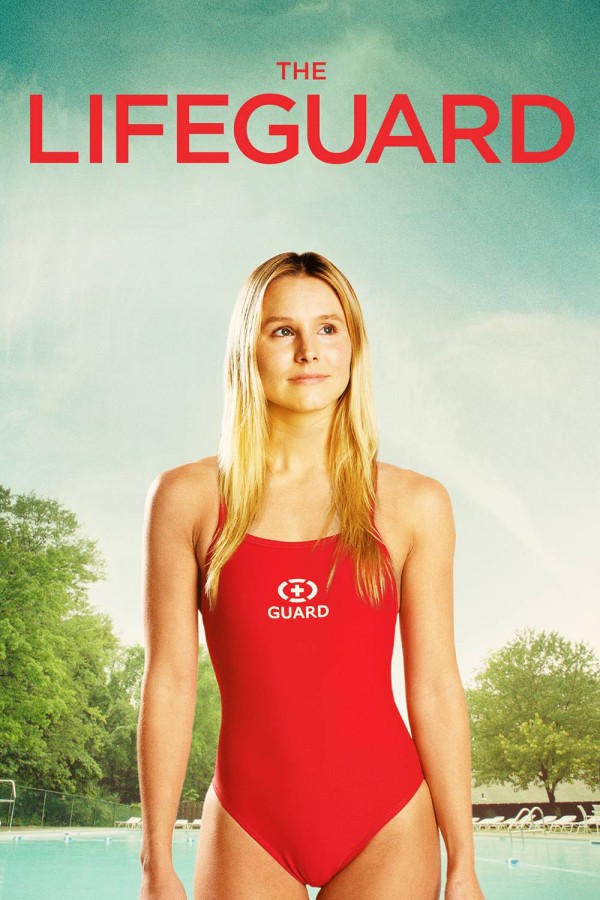

The Lifeguard (2013)

This movie comes from the horrible genre that hybridizes the ordinary film with atmospheric music videos where the main point seems to be the lyrics of the pointlessly generic alt-rock songs. Despite that, which adds about a half-hour of utter dreck — both musically and in storyline — to this film, The Lifeguard makes a singular point: what we think of as adulthood is not what adulthood actually is.

Centered around the type of single-pivotal-event plot that has been trendy since the 1990s, this film focuses on a journalist who leaves behind her city life to go back to her hometown eleven years after high school ended. Now 29, she seeks escape back into the idyllic and simple world of her job as a lifeguard, her friend group who spent all their time just hanging out and getting loaded, and having someone impossibly impractical to fall in love with. She re-creates this lifestyle, only to have it slowly confine her and reveal its own emptiness, as contrasted to the pointless emptiness of the lives that everyone older than 18 has taken on because they think that this is the way people are supposed to act. Eventually, a non sequitur of an event provides the blasting cap to this fertile dynamite and the illusion unravels, and she goes back to the city and her friends go back to their lives, but with one crucial difference: they now realize that appearance of adulthood is destructive, where the real thing is more nuanced.

The movie peaks with this line:

Look, Jason’s been through enough in his life already.

Real problems. You get me?

This thing with the lifeguard — things happen.

Keep moving or die.

Much like the immortal lines “You’re a white suburban punk, just like me,” from a movie of greater importance, these key lines reveal the fundamental message here: adults are horrible because they get caught up in non-reality and invent fake problems out of it, when what must really be done is clear only when the fog of conformity passes. In this case, the fog of conformity consists of obligations that the best friends of the protagonist Leigh can perform but realize are empty, despite dedicating their lives to them. Leigh, as the high school valedictorian who now retreats home in failure, finds herself having failed in the adult world by having treated it too much like the image of an adult, while not paying attention to her inner voice demanding more from life than the obligatory career. There is also a painfully obvious symbol in there that is excessively emotional, but caters to Leigh’s vision of herself near the start of the movie. The film itself relies on the aforementioned music videos, lots of porny explicit sex, and an abundance of scenes of 30-somethings partying with teens in a melange of images that can be safely slept through because the point is made with the first scene in every case. As with most modern movies, the problem is that to convey an idea it must be distilled to something that can fit in a single Twitter tweet, but a movie cannot fully expand from such a simple point and so much of this movie is well-filmed but uncompelling filler.

While the acting in this is not terrible, it also will win no awards because the scenes are too obvious to permit nuance. Polish/Scottish-American Kristen “Dead Eyes” Bell manages the lead role well, but has too much of a studious and detail-intensive approach to performance that misses any kind of human spark. Ironically, a film about how being a good study-buddy is a failure hires a study-buddy for the lead role. Other actors, including the comically-named Mamie Gummer (a descendant of the Streep dyansty) perform well but are given gunk for lines because every scene is obvious and most are repetitive of previous scenes (with a music video between). The struggle this film faces is that it is cut from genre template, and so it has to conform to the kind of mind-numbingly obvious patterns that render any spontaneity dead so that every person in an average audience, even the fundamentally blockheaded, can understand it. This trashes any recommendation from sensible people to go see this film. It would be better as a micro-short story:

Leigh lived in a cubicle punching out the clock work. She saw how cages kill, so obsessed by nostalgia she returned to her lovely, green, leafy, pleasant hometown. There she found her old friends stagnant too. They started smoking weed and drinking beer with the local kids, but could not catch the vibe. They had matured past it, but what they matured into did not work either. They demonstrated hipness but frustration came from within. Everyone says naughty words a lot and the sex is really porny. Then, something big happened and everyone used their big people swear words twice as frequently. They saw the emptiness of nostalgia, and also the emptiness of conformity, so quit conforming and got on with adult life. There were also indie rock videos that demonstrate how rock music is entirely forgettable except that people like the lyrics because they make them feel validated. I hope I never have to see this film again. Amen.

What makes this film rise above background hum is its insight regarding adulthood. Nostalgia is horse feces; well, so also is pointless conformity to expectations that do not produce reward, says this film. It almost feels like an Ayn Rand-style capitalist jihad to remove all activities which do not produce immediate results in self-interest, simply because that indicator — return on investment — usually separates the pointless political activities from that one-tenth of human energy expenditure that is actually necessary. The Lifeguard will win no classic status, nor is it really worth watching. But it makes one point well and we will all be fortunate if that one is assimilated into popular culture. Unfortunately, it obeys the observation I have had about mass-culture movies trying to be critical of mass culture, which is that they either must end in returning to the herd or by destroying everything. The Lifeguard takes the former path, unconvincingly.

Tags: adulthood, alienation, conformity