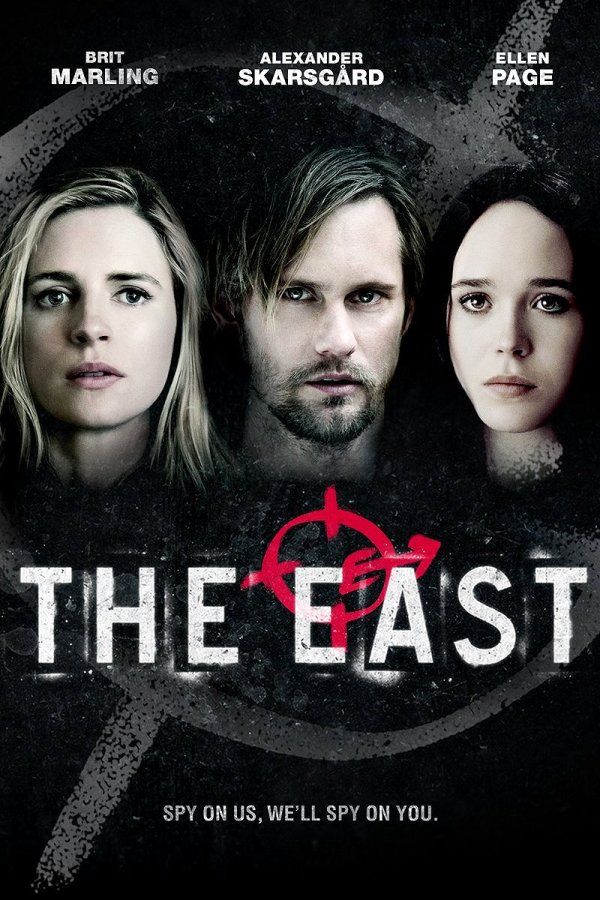

The East

You can already guess how this movie ends simply by reading the premise:

A young woman who works for a giant soulless corporation is tasked with infiltrating an anarchist network of ecoterrorists. The writers thus have about 120 minutes to convince us why she would want to give up a bland but reliable boyfriend and an exciting job to continue eating out of garbage cans with social pariahs until she’s thrown in prison for twenty years or more, after which she’ll spend her remaining days refusing entry into Walmart to people who forgot to put on shoes. There’s no rule that says you have to surprise your audience to be a great storyteller. The authors succeed at the only meaningful goal any artist can have, which is to leave an impact on your audience.

Despite a budget of $6.5m the movie yielded only $2.4m. Those who funded the project arguably made a miscalculation in that the American public simply isn’t ready to side with a gang of ecoterrorists. Whenever this topic is addressed, it is generally with thick layers of romanticism (Avatar) or testosterone infused nihilism (Fight Club). Honesty is this film’s greatest virtue: the authors do not hide behind irony, edgy metaphors and sleep deprivation induced mental disorders that leave them with a plausible escape route to proclaim that we have all completely misunderstood the film. The authors take their stand in act as well as deed and we’re free to take it or leave it, a kind of courage not a lot of people have when it comes to a topic like this.

The first reason you should watch this film is because it shows you what we’re missing. The main characters have lives that are filled with hard but meaningful struggle. They depend not on the outside world but on each other. Together they unlearn the values we were taught by modern civilization. This movie shows what makes religious cults, anarchist communes and other social experiments so appealing: participants become part of new tribes. Individuals in these situations meet people who are similar to them and with whom they can be honest to and share everything with. This is the exact opposite of modern Western society where we are all isolated from each other, as studies now show that a quarter of all Americans have nobody to confide in.

The second reason to watch this film is because it happens to ask the right questions. We’re horrified by violence and terrorism, but why exactly? If you happen to be poor and someone decides to dump toxic waste into your community that will eventually give some people cancer, is that violence? Why are we more horrified by deaths from terrorism than deaths from air pollution? Why are we more horrified by deaths caused by political statements and sheer hatred, than deaths caused by greed and indifference?

There exists a social class within Western society that benefits from maintaining a narrow definition of violence. These plutocrats propagate Nietzsche’s slave morality. If your child dies from leukemia because your land has been turned into a chemical waste dump, these propagators of the slave morality expect that you will write letters, to them, the local media and twitter accounts, in the hope that your outrage over your violation succeeds at stealing attention from some other outrage. If you’re really audacious, you’re even allowed to start a lawsuit against them and settle out of court, trading your dignity for thirty pieces of silver in the process.

As Nietzsche noted, the monster really doesn’t mind when you fight against it by its own rules because that helps it to assimilate you. In the process of your Pyrrhic victory you have taken on its culture and its values and became personally invested in its success because it is now what guarantees you victory. Look into the mirror, see the monster staring back at you. When you’re checking on your cell phone how much further the SP 500 has to rise before you can retire to your permaculture farm, you might just notice a tiny little smirk in the mirror.

Tags: ecoterrorism, emptiness, Friedrich Nietzsche, modernity, movies