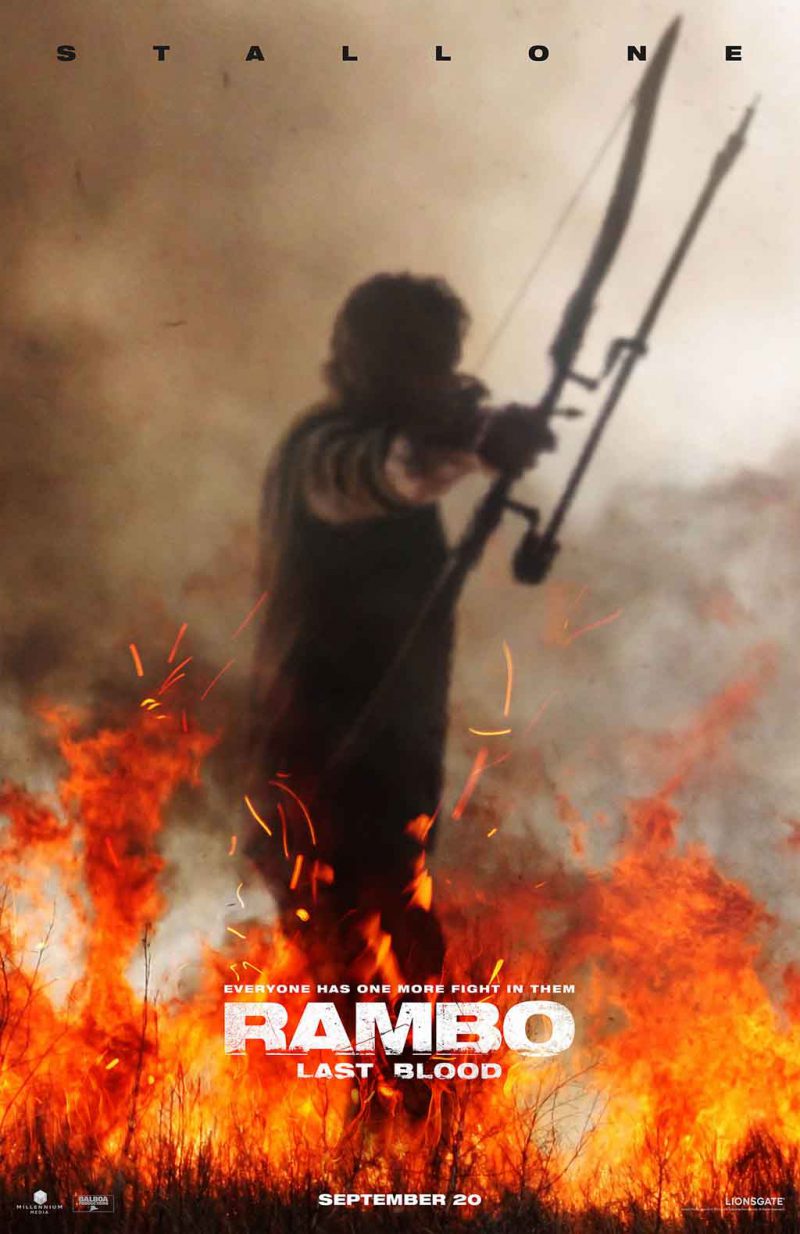

Rambo: Last Blood (2019)

Cinema from this era will be remembered for its pattern: a long emotional lead up to a violent conclusion with all of the variation of inertia. Once the decision is forced upon the characters, who present themselves as lambs for the slaughter, they act without thought, morality, or emotion.

Rambo: Last Blood may show us the apex of this sub-genre. In this film, an adopted daughter goes to a third world country, encounters somewhat predictable bad results, and then our hero is abused to the point where he goes on a quest for revenge.

This contrasts the first Rambo film, First Blood, where a drifter is removed from a small mid-American town and decides instead to demand his right to stay, at which point he is hunted and must retaliate. Same plot on the surface, basically, but less of an innocent victim finally gets revenge motif. In the first Rambo film, he was fighting for survival; in the new one, he is fighting for a principle even when all hope is gone.

A “slow burn” approach to development as used in this film suggests a different emotional state of the audience. At the time of First Blood, America was dealing with the fact that it rejected the soldiers of one of its noblest wars out of a middle class bourgeois disdain for complex emotional problems and possibly lowered property values, echoing the voters who supported the war until it became inconvenient and then turned tail and fled, betraying the men in the field.

Psychologically, in Rambo: Last Blood we see a different archetype, mainly the scarred person just trying to have a normal life, but the bad (represented here by the third world) will not stay away, so they present themselves as a victim — as John (Rambo) does in one Christ-like scene — so that they have the mental clarity to act as warriors, eliminating the bad.

Not as directly stated as the first movie, and perhaps more artful and clever in how it is written, Rambo: Last Blood makes nowhere near as strong of a point. We can sympathize with Rambo the drifter; Rambo the guy with a normal life who must take revenge strikes us as someone who has missed the point and, like the modern West, is slamming the barn door after the horse got out.

In particular, the script tries so hard to be strategic that it leaves all sorts of holes in its logic and burns screen time with inefficient scenes that in theory produce emotional quanta, but from the 30,000-foot perspective of a year passed, seem only to conceal the core issue: in First Blood, Rambo wanted to be able to live; in Last Blood, he has found that a normal life will be destroyed anyway, and simply wants bloody revenge.

This tells us quite a bit about the psychology of the West at this time. Sylvester Stallone, himself an ethnic cipher, tapped into the desire of non-WASPs to take part in WASP society as well as the national attitude of confusion, guilt, embarrassment, and trauma over the Vietnam War. Now he taps into our new war, which is yet undeclared and ambiguous to most, namely the first world versus the third, both externally (globalism) and internally (diversity).

The movie begins with Rambo on his Arizona ranch, living with his adopted Mexican family who are thoroughly Americanized and innocent. Without getting into the particulars, which are both spoilers and obvious as bones in a field, this innocence is horribly violated, and Rambo must do what he does best, as he did in First Blood: lure a moronic and numerous enemy into attacking him, at which point he uses his hybrid Special Forces and Viet Cong tactics to comedically exterminate them with zero regard for human life.

Symbolism of this nature appeals directly to our psychology. This movie says that no matter how much we try to accommodate the third world, its problems remain its own, and our only response can be to destroy those problems and abandon the third world, much as Rambo eventually divests and separates from his third world surrogate family.

Tags: john rambo, movies, sylvester stallone