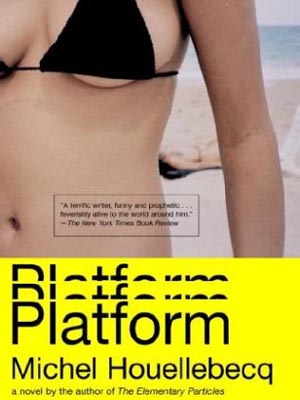

Platform by Michel Houellebecq

Platform

by Michel Houellebecq

Vintage, 272 pages, $11

Of all the modern writers out there to attempt to inherit the spirit of the past, only Michel Houellebecq and a handful of others have a fighting chance. That is because their books are about issues, not lifestyle accessories and fashions.

Of all the modern writers out there to attempt to inherit the spirit of the past, only Michel Houellebecq and a handful of others have a fighting chance. That is because their books are about issues, not lifestyle accessories and fashions.

Your average modern person, thinking in terms of equality which makes all things identical except for surface attributes, will look at different areas of life and try to sketch them by appearance and not substance. There is no conflict, nor any evolution as a result, nor a real sense of people giving a damn. All they do is adorn themselves in new types of appearance and new categories of social activity and hope it gives their lives meaning, which of course it does not, so those books end in either crusades for the disadvantaged or “uplifting” discovery of new meaning in themselves. This tautological modern propaganda of course conveys nothing which makes it the perfect background music or scenic wallpaper to a life full of job, commuting, shopping and voting.

Houellebecq takes the opposite approach, which resembles harsh industrial or heavy metal music, or even the Gothic tales of horror of the past: he shows us something that is so perfectly ugly on the surface that its absurd excess provokes bitter laughter, and then within it, discovers something of meaning — and then smashes it down to keep his books from becoming Hallmark Cards or Lifetime Movie Network movies with false cheer that obscures what in reality would have been a grim end. The primary reason to read Houellebecq is that he is hilarious and out-of-control, raging with an acetic mockery of the world, smashing idols and shish-ka-bobing sacred cows. Through this process, he reminds me most of Tom Wolfe and Michael Crichton, who also dedicated much of their ouvre to skewering pleasant illusions and explicating complex truths.

While his masterpiece remains the untouchably ludicrously bleak Elementary Particles, with Platform Houellebecq finds a happy balance that produces a more readable, clear and direct novel with less of the metaphorical layering that both made Elementary Particles a delightful voyage of discovery and somewhat dense and impenetrable. Platform is plain spoken experience in narrative form.

The book’s protagonist is Michel Renault, who like the creations of many great authors (Celine, Fitzgerald, Burroughs) is a reflection of the author writ in simpler clearer terms, a low-level functionary in the bureaucracy of the French government. Readers of past Houellebecq novels will recognize this archetype from all of his books, starting with Whatever (a gem of dystopian nihilism that pointed out what all knew but could not say, which is that modern jobs are soul-crushing jails that make people wish to self-destruct and take society with them) and continuing up through this present book. In this case, however, he has made Michel less neurotic than previous characters, and more inert, like Holden Caulfield written by an adult.

Michel is numb and stumbles through life with his personal void sucking in things around him. His job is meaningless, his friends nonexistent, and his actual connection to reality tenuous, so he’s left with pleasures of the body. In this case, that means a life of TV dinners, pornography and prostitution. Eventually, he fumbles his way into making the decision to go to Thailand, which is a beautiful place but for decadent Westerners, is primarily known for its access to cheap and easy sex. In Thailand, he has a number of experiences which have that “slipping into a warm bath” effect of being both not unpleasant and yet vitiating to the soul, before he finally manages to encounter a younger woman. She has an internal void as well, but has recognized hers and called it by name, and so she is able to embark on a new mission statement. Her goal in life is to re-connect to it through the sharing of pleasure with people she cares about.

Houellebecq writes about Valerie with great tenderness and creates in her his most haunting character. We see her early life, her loneliness at work, and how — in opposite to Michel — she has embraced selectivity and the notion of pleasure, especially finding pleasure through the giving of pleasure, in life. Houellebecq works sexuality into a masterful metaphor where it is either pleasant and empty by being isolated as a physical event, or dangerous and compelling by being integrated into life as a whole. Michel and Valerie eventually become an item, and at this point, Houellebecq stops talking about Thailand and shows us the guts of the West, which is where its doubts come from. Through a tour of the disavowed underbelly of rotting Western culture he shows us the fundamental dynamic of masochism and hatred that plays out in other forms throughout the book, and through what he diagnoses as the cause of the collapse of the West.

‘What scares me about it all,’ she said, ‘is that there’s no physical contact. Everyone wears gloves, uses equipment. Skin never touches skin, there’s never a kiss, a touch or a caress. For me, it’s the very antithesis of sexuality.’

She was right, but I suppose that S&M enthusiasts would have seen their practices as the apotheosis of sexuality, its ultimate form. Each person remains trapped in his skin, completely given over to feelings of individuality; it was one way of looking at this. What was certain, in any case, was that that kind of place [an S&M club] was increasingly fashionable. (191)

Rhythmically, this book proceeds more smoothly than any Houellebecq to date. It is poetic, but without abrupt motion; it’s a sine curve stacked against a sine curve, so that we see one motion decline and another rise before the two reach a state of either pure harmony or pure disharmony. In it, he makes his metaphor join the story itself and, while like all Houellebecq books this one is still too obedient to reality to go for a Disney ending, there is no shortage of profundity. This book can shock people awake.

Houellebecq writes (via translation) in the style of classic European novels from the 1900-1935 period: clear narration in an abstract voice that removes the personality and so shows us the character through the character’s reactions to events, not any particular voicing of those ideas. Although this is a first person novel, and with only a few exceptions those are odious and simplistic, this book manages to be one of the exceptions. It is clear, powerful and resonant.

Tags: Books, literature, michel houellebecq