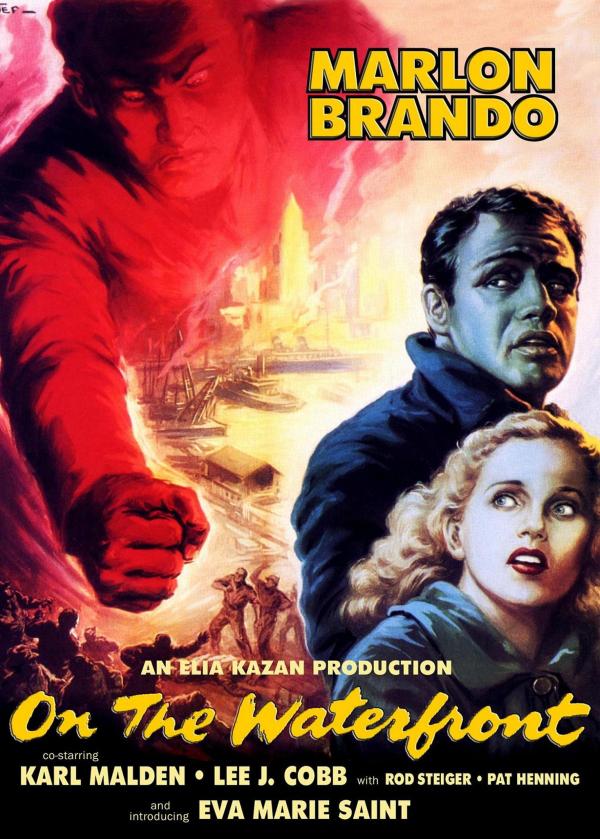

On the Waterfront (1954)

Movies are like rock music always playing a catch-up game to prove they’re as good as the classical variety. To this end, no shortage of “weighty” but not “heavy” topics come out, meaning that important things are discussed and then resolved in a petty way to allow people to return unhindered to their jobs without concerning themselves about long-term problems. It’s like fighting a symbol in that in the fantasy world of the movie, you beat the symbol once and the problem goes away. Shopping awaits.

On the Waterfront, being an antiquated piece of film, could well be an important forerunner of the type of pompously “serious” and fatuously empty movies we saw in the 1980s. Basic theme is this: conflicted character in a bad situation discovers a higher moral truth, and with that in hand, sacrifices himself or herself and does the difficult thing, in the process being misunderstood both by his unimpeachable moral guides (women and priests, or modern analogues, usually black characters in buddy films and psychologists in urban dramas) and his former colleagues in crime or deviance. The showdown occurs, and the now-good character toughs it out in some Jesus analogue situation where he fights but allows himself to be beaten, then rises again when the crowd of one-dimensional onlookers is inspired by his acts and come out cheering. At the end, bad has been brought to light, and good has been achieved in his soul, and to the cheers of his comrades he is accoladed as a new Christlike hero. A gigantic cliche, it’s a distillation of the ancient art form of tragedy, except all that made tragedy noble has been replaced by answers benefitting an ethic of convenience, albeit with the momentary struggle for right.

This movie fits neatly into those notches and thus hitched rides the train to its conclusion. Tough bad guy Terry Malloy got some bad breaks as a boxer because he took money to throw a fight, and now at age 30 he’s an unmarried useless bum whose primary activities are raising pigeons. As he explains himself, there are pigeons and hawks, and if you’re not a hawk, you’re going to end up a meal for one. Enter the clueless ingenue Edie Doyle who has actually been at religious school, and allied with her local large-nosed priest, has decided to fight the mob that controls non-union labor on the waterfront. Characters are one-dimensional; the mobsters are pure greed, Edie is pure clueless good. Terry is the conflict hinge in this because (as the rock-heavy-handed symbolism reminds us every time he’s seen feeding or holding a goddamn pigeon) he likes the pigeons but wants to be a hawk because he’s afraid.

After numerous revelations, and countless tributaries of personality drama, he discovers his inner self and confronts the mob bosses by testifying against them. As soon as the crowd is shown the light of truth, etc., they begin to change, but they’re still afraid to take on the mob until brave Perry calls out the mob boss and fights him, loses when the guy calls in his goons, and then marches back to victory after which all others follow him. Conclusion: good wins over evil. Cynical analsyis: the one-dimensional mob boss is a symbol of bad, and government and clueless women a symbol of good, but nothing is said about the systemic problems which produce more mobsters, or what to do about them. It is assumed that showing people the truth allows an easy victory.

Even the struggle for Terry’s soul is completely hollow in that he does not confront a complicated moral choice, nor does he triumph over it, but shifts from one side to another. His struggle is not internal but external: he is trying to find a place, not defining his soul, even though the movie does everything it can to convince us of the opposite. If life were so simple, would we need movies? The sense of being lulled into a comfortable sleep is overpowering. While cinematically there are some beautiful moments, and the soundtrack is in parts admirable, the complete shallowness of this work makes me think the only people who like it are those who are looking for an excuse to justify their ethic of convenience. Go watch Chinatown or Apocalypse Now instead, and face the darkness and light of the soul, instead of picking two packaged products in a simplistic and symbolic choice with no relation whatsoever to reality.

Tags: archetypes, movies