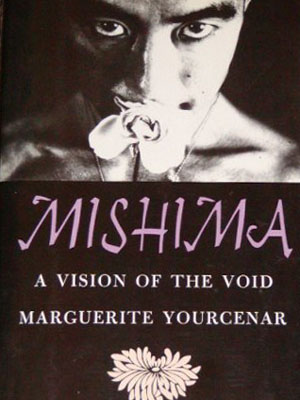

Mishima: A Vision of the Void by Marguerite Yourcenar

Mishima: A Vision of the Void

by Marguerite Yourcenar

151 pages, Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, $18

As a friend once noted, humanity has excelled in one thing over the past thousand years: producing alienated geniuses who articulate elaborate visions of our path as a steady walk to soulless doom.

As a friend once noted, humanity has excelled in one thing over the past thousand years: producing alienated geniuses who articulate elaborate visions of our path as a steady walk to soulless doom.

Yukio Mishima was one such person. Born sickly, homosexual and into a family that thoroughly alienated him, Mishima became a prolific voice for criticism of the modern era. In particular, he resisted “Westernization” of Japan with its modern conveniences and consequently, an amnesia concerning how to strive for beauty and live with honor.

Marguerite Yourcenar writes of Mishima both through his art and as an object of art. Part biography and part literary criticism, Mishima: A Vision of the Void attempts to create a double helix that pairs Mishima’s ideas and expressions in life with his literary visions. It succeeds at times, sometimes with great insight, but for the most part this book moves slowly through somewhat airy analysis.

Where this author shows her power as a writer is in understanding the highlights of Mishima’s life as expressed in his books, plays and essays. Were this a 20-page thesis paper, it would be startlingly brilliant with twists and turns revealing greater depth at each moment. That content is still here, but afloat in introductory material and conjecture that while it may in part be an artifact of translation, burns so much space on the obvious that it leaves the reader wondering whether any purpose to it exists.

Then again Yourcenar does not have the easiest task. From a brief reading of Mishima, he is both dense with symbolism and conceptually inextricable from the world the author has created, and so any analysis of his books involves somewhat of a retelling of the story while saturating the reader in foreshadowing of its concepts. The idea of an introductory book to Mishima could well be entirely apocryphal.

However, it would be hard to criticize this book for not taking its subject seriously. Mishima is treated seriously, even reverently, with a compassionate analysis that brings out the most meaningful and powerful moments in his work and life. Biographical data is thin in part because of this, since it does not enhance our understanding of him other than a few pivotal moments, which are highlighted in their intensity.

For someone who wanted a revival of traditional Japanese culture, Yukio Mishima (a pen name that conjures up imagery of a snowy forest at the base of a mountain) thoroughly Westernized himself, both in lifestyle and in literature. He took inspiration from Western Romantics and the Christian martyr Saint Sebastian, who was killed by Emperor Diocletian for his refusal to disclaim his Christianity.

Yourcenar finds in Mishima a person of intense expression of will: a sickly boy who made himself into a bodybuilder and martial arts expert, the son of a civil servant who became a literary wunderkind, and most importantly (perhaps) a celebrity who opted for a violent and painful suicide instead of a fawning public life.

In her view, Mishima’s suicide is essential to an understanding of his life, which expressed the same beliefs he developed in his writing. For Mishima, the Idea shone above the daily entanglements of mortal life and even love, much as his characters are all incarnations of ideas, with vital identifying markers (such as patterns of birthmarks) passing between characters who he identifies as reincarnated versions not of one another, but of the same idea, much like the avatara of ancient Vedic faiths.

It is not believable that Mishima, who for six years had been preparing his ritual death, should have mounted this complicated scenario of speaking to the troops and making a public announcement prior to his death with the sole intention of setting the stage for a double departure. Simply — and he explained this point in his debate with the communist students — he had come to believe that love itself had become impossible in a world bereft of faith, and compared two lovers to the two angles at the base of a triangle; the Emperor whom they reverse is the third. Replace the word Emperor with the word cause, or God, and you will arrive at the notion of a belief in transcendence necessary to passionate human love… (142)

It is the quality of such literary analysis that makes this book worth reading. For every ten pages that wax too literary for the practical reader, or seem flights of fancy departing in flocks, there are insights that only another writer of fiction from the same era could understand, and Yourcenar shines in these areas.

Better biographies of Mishima, and more extensive analyses of his works, may exist elsewhere. This book however is intriguing for its short length and breadth of attempt, which is not to tell us the details of his life or cover every possibility, but to explain Yukio Mishima to those of us from a time that would not understand his sacrifice, or the love or beauty that motivated it.

Tags: biography, Books, marguerite yourcenar, yukio mishima