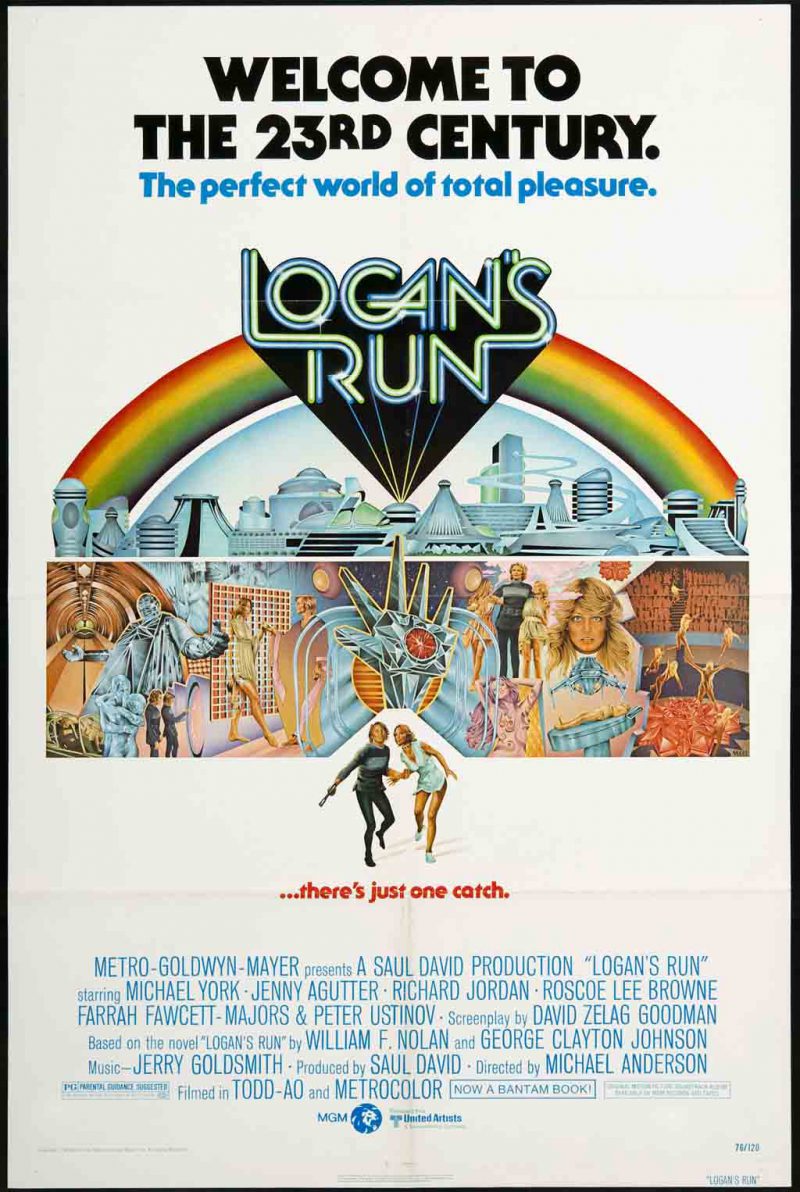

Logan’s Run (1976)

After the Great War, people realized that our world was headed down a very bad path. It was not so much the sacrifice of the war, which left many good people dead, but the fact that nothing seemed to have been achieved. We killed our brothers, democracy reigned, and all of our problems got worse.

That in turn spawned two great genres of proto-science-fiction. The first, dystopian, projected the wartime propaganda that we would become victims of some outside influence; the second, utopian-dystopian fiction, warned that we were most likely to make ourselves victims by pursuing illusions.

From that second stack came writers like Aldous Huxley and C.S. Lewis, both of whom wanting to show us that if technology and democracy empowered human desire, we would take ourselves to a dark place disguised as a place of light. Nearly a century later, we can congratulate them on a job well done.

Logan’s Run comes from the utopian-dystopian mold and roughly follows the outline of Brave New World: a futuristic, science-based civilization shapes itself around human desire, specifically sexual desire, by managing birth and death to ensure that everyone is attractive and willing.

In this shining future, everyone lives in a massive shopping mall type management environment. Everything is spotless. For entertainment, they go on a far-out version of Tinder that delivers members of the opposite sex to their stylish apartments for a night of joy. People essentially live for lust.

Their jobs are easy and simple, consisting mostly of pressing buttons while the computer does the rest. Their days are spent mostly in play, and everyone dresses like they are ready for instant sex. There is only one glitch: when they turn thirty, they get “renewed.”

Renewal takes place through an event called “carousel,” where the scientific and computer-assisted futuristic society transfers people into new, youthful bodies through a process that looks a lot like killing them. However, the population seems oblivious, since it is not their turn to go.

No one has any reason to steal and no one has want. In fact, everyone experiences great pleasure, all of the time, and they are vastly social. Their only real trouble are “runners,” or people who try to flee this utopia-dystopia as they approach age 30.

Enter Logan 5, an enforcer whose job it is to hunt down these runners and kill them. As his clock suddenly advances, he finds himself questioning the entire system, and has to decide whether or not he will flee it and, if so, whether he can reject his allegiance to the previous system.

Filmed in glorious 1970s technology, Logan’s Run has lots of cool special effects, most of which mostly stand the test of time. It also produces a genuine atmosphere of fear as the viewer realizes that this shiny plastic world is almost impossible to criticize or evade. It has dominated nature and all else and, objectively, has nothing wrong with it, at least if you are under thirty.

Like many movies of this era, this film runs long and features scenes based almost solely on dialogue or action but not both. Sets look like they were designed for theater, and efficiency is not the goal; it seems more intended to be atmospheric in an early way, soaking you in the milieu so that you feel it rather than think it.

Without giving any spoilers, a reviewer can say that this movie roughly follows the plot of Brave New World, with a few twists, including some so bizarre that they are nearly incoherent, giving them film a surreal varnish that helps suspend disbelief of this disturbing futuristic world.

It seems very well placed in its time, only a few years after “Don’t trust anyone over thirty” became a new media meme. Bursting onto the scene in the middle of the sexual revolution, its fascination on sex is less pervy than an allegory to consumerism, showing men and women as if they were gadgets.

As with many 70s movies, the margins tell more than the story, and the understructure of narrative here shows us how useless and credulous people have become, and how empty they are to be satisfied with this plastic world of transient pleasure. Unlike in dystopian fiction, here the enemy is not without, but within, and our own vapidity unleashed by a perfect egalitarian-technological society reveals our emptiness.

Even more, it shows us people in worship of a false religion of technology, trusting the very machines that kill them to be supreme arbiters of what is true, without really knowing how the whole system works or what it does behind closed doors. The cult-like participation is designed to give you the creeps, and forty-three years later, it delivers that message perfectly.

Perhaps tame by our standards in an age of instant-on pornography and dating that uncannily resembles that in the film, Logan’s Run delivers the same warning that 1984 did, except that it reminds us that we are in the driver’s seat and if dystopia is created, it will be by our desires, narcissism, and selfishness that it comes to pass, and still we will be miserable.

Tags: dystopian, film, logan's run, movie