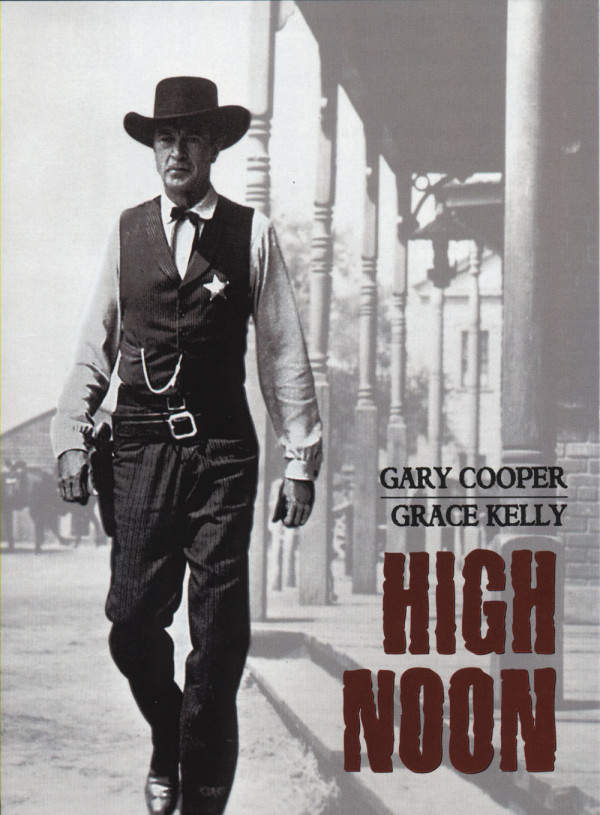

High Noon (1952)

Taking up the same underlying material that propelled the tales of Jesus Christ and Socrates, High Noon involves the sheriff of a small town who has just retired to get married. Most agree that he has reformed this small town and made it safe, and they want him to just sign off and ride away. Then comes news: the brother and allies of a man he put away for murder, but has been exonerated, await the arrival of this radical killer on the noon train, at which point they plan to do in the sheriff. The film takes place on one morning in the time leading up to that event.

High Noon makes for difficult watching because it transports us to another time and then metaphorically shows us the eternal human struggle: do we acknowledge reality and act on it, or retreat into the comfort of denial, narcissism, compensation, apologist and solipsism? This film ultimately takes the form of a psychological drama with most of it focused on the efforts of the sheriff to prepare for the confrontation and perhaps to find someone, anyone, who will take his side. He faces four gunslingers and any knocking down of the odds would radically increase his chance for survival. Instead, the townspeople invent a creative series of excuses: it is easier and cheaper to work with the bad guys, the job is thankless, the town is not worth it, and the odds are too bad. Somewhat shocked that the people who have benefited from his transformation of the town from an unsavory place to a successful one have nonetheless forgotten this and effectively betrayed him, the sheriff makes his will, and prepares himself to go it alone.

Expert cinematography and editing use techniques ahead of their time to increase tension in a steady upward path interrupted by many strange detours into the human mind. Gary Cooper makes the lead character complement that with his laconic, forthright and masculine character. He makes the sheriff into a character both robotic and expressive, a nervous constant searching gaze complementing his ready hands. This portrayal seems more accurate for a smart man facing multiple enemies and near certain death than the usual flippant cowboy stereotype. As critics noted at the time, nearly everyone in this movie is seating, a psychological device that enhances the tension within. This builds up to a series of combat scenes that, as far as a movie can be, are intensely realistic. Unlike most cowboy movies, the bullets here feel real, and the gunplay is not showmanship but lethal intent. Each character works systematically to act as programmed, drawing the movie toward is deadly conclusion.

Characters in this film — and it is ultimately a cinematic book, where story drives visuals and not the other way around — struggle with the tensions of human life in a way that shows how frustratingly simple and broken we are. The new wife who turned Quaker to be pacifistic after her brother and father were killed must decided whether having a good outcome is worth an evil method, and whether evil can be banished by method (non-violence) at all. The townspeople who acknowledge that the sheriff has saved the town from being a criminal wasteland, but want to believe that nothing needs to be done except absorbing a few costs created by these criminals. The deputy enraged by his own cowardice, lashing out at the sheriff for making all of them look bad by not knuckling down to be a good cuck chicken-man. Finally, the sheriff himself, aware that he is not wired in a way that allows him to ignore imminent evil, and giving himself to his fate with grim determination even as there is little chance he will survive.

Published at the height of the Korean War, High Noon served as a reminder that people would rather sacrifice truth for convenience, and it takes rare and uncivilized men to reverse that — and that these men are our only hope. While the useful idiots, armchair critics and chattering neurotics of the suburbs will always prefer inaction and making deals with the devil to confronting evil head-on, the path to destruction begins with those steps, and no matter how it is justified as prudent, moral, pragmatic, pacifistic or compassionate, such behavior is always the same thing: cowardice. Resonant with truth of human behavior as told in a setting that is both comfortably removed and yet wove into our DNA in the West, High Noon teaches the point of Socrates and Jesus that reality is not optional and cowardice is death.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SkNu4-sSglY

Tags: cowardice, cowboys, cuck, films, gary cooper, jesus christ, socrates, useful idiots