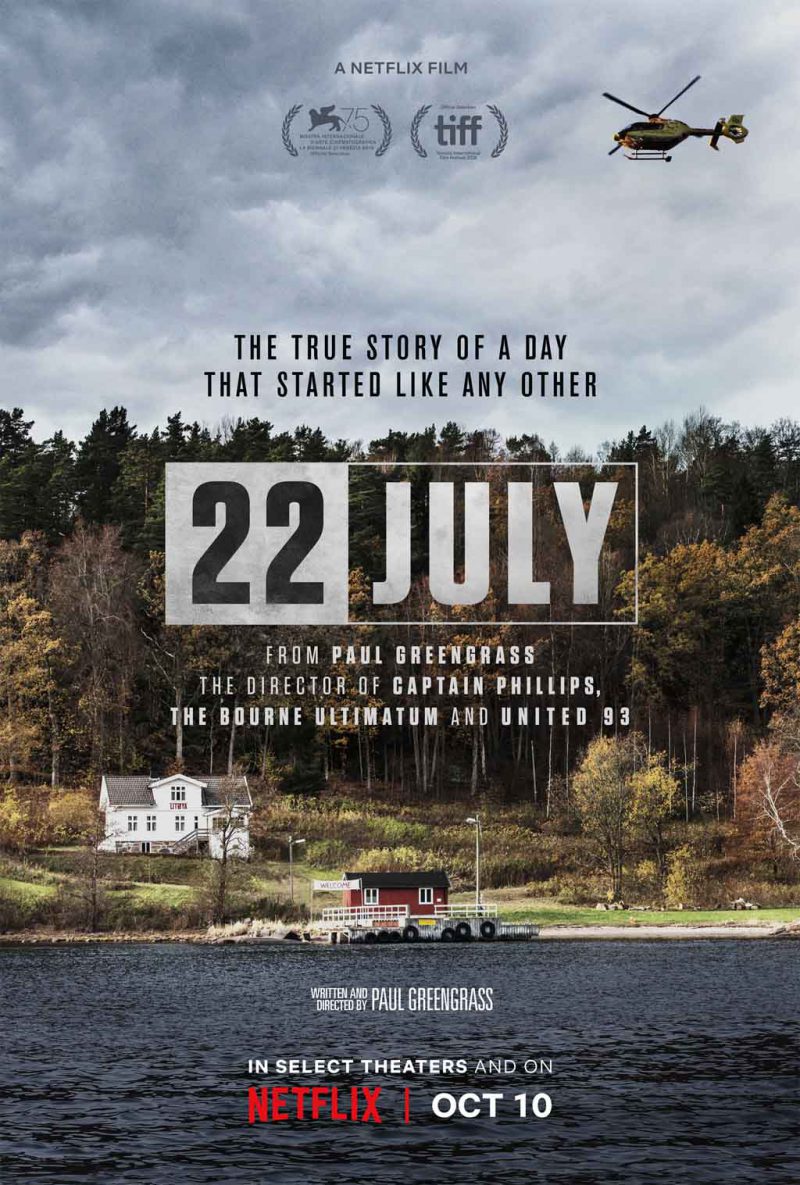

22 July (2018)

22 July

Netflix, October 10, 2018

Dir: Paul Greengrass

At one point in this somewhat binary documentary, Anders Behring Breivik (Anders Danielsen Lie) asks his lawyer if he can call the prime minister of Norway to the stand. “Norway is not on trial here; you are,” sedately snaps Geir Lippestad (Jon Øigarden). Breivik considers, then asks, “Are you sure?”

Ultimately, we the audience cannot be sure. This documentary attempts to be two things: an emotional final statement by one of the teenagers who was shot, Viljar Hanssen (Jonas Strand Gravli), and a dispassionate retelling of the events leading up to that point. The latter wins this documentary points for objectivity, where the former shows its intent all along. It means to lull you into the experience, then hit you with its only intensely personal drama, which serves as the talking point of the film and explained why Netflix produced it.

Despite that somewhat inglorious ending, the film has its merits. The first few scenes of Breivik executing his plan, methodically and calmly, while society stagnates around him — shots of dreary Oslo, his detached mother, and the everyday oblivion of Norwegians intersperse with his military-style preparation — provide a growing sense of ominous doom. Intensity rises as we realize that events are about to leave behind our happy society and its rules and get primal, and then he lights the fuse in his explosives-packed van parked outside the prime ministerial office and the movie goes into action mode.

At this point, Norway goes on trial. Shots from the Utøya summer camp show us Leftist indoctrination in progress by careless, neurotic people. The teenagers themselves are portrayed as vapid and thoughtless, bleating out the right dogma for approval from their peers and parents. The parents reveal themselves as fundamentally self-centered, more concerned with career and popularity points than family. Norwegian society itself seems senescent, sleepwalking through the motions of pointless activity, and oblivious to the rage it builds in people who notice things. The scenes of Breivik’s mother, disconnected from her son and herself, wandering around in a mild mental health crisis, symbolize all of Norway and through Norway, represent all of the calcified West. Its pretense aside, our modern society is as empty as the dogma repeated by characters in the film.

Up to the time where Breivik begins shooting, the audience sits in a kind of shock, as in a good horror film. We are trained to be unable to believe what we see unfolding. When Breivik starts shooting, we see the same stupefied oblivion to reality on the faces of the teenagers, and find ourselves cheering for him as he hunts them down, since they are too detached from common sense to do anything but cower and ineffectually flee when the lake is not actually that wide and they could easily escape. The Norwegian police, unprepared, strike us as inept, as does the response of citizens, who stump around in a stupor trying to follow procedure when it is clear that the agenda is to wake up and figure out the situation. “Wake up!” this documentary screams at the West, as if acknowledging Breivik as effect and not cause, which goes against the narrative of we dindu nuffin that comes from the Left as a whole.

The horror film nature of how these scenes are filmed orients us toward those we hope will survive, and the only person without illusions proves to be the shooter. In your average horror film, a group of people confront an unknown terror and then must struggle within themselves to snap out of the civilization-induced slumber, recognize what is going on despite not being “educated” to see it, and then act in a way to survive or, ideally, defeat the evil. In this film, none of the victims snap out of their daydream, and so they remind us of bit characters in horror films who die early by having tantrums, going into denial, or otherwise being wholly ineffective. Not only are the teenagers and their counselors useless, but so is most of Norwegian society.

Frustration with Norway, and through its symbol the modern West, erupts through the scenes of frantic attempts to mobilize Norwegian police and even just get a helicopter in the air, as well as the short shots of lengthy committee meetings, legal meetings, and the day jobs that the parents have, showing us that people are wasting their time and that they are existentially miserable but no one wants to be the first to admit it. Characters talk about nothing but the event, and when they do not have that as a topic, their conversation mostly consists of “how are you?” “I’m fine” “Want to watch a movie?” and other small talk. We see a society which has made itself trivial by doing the “right” thing, and how that leads to a daily existence of paperwork, insincerity, navel-gazing, and frenetic denial of reality.

If this film has a thesis, it might be that Norway, indeed, is on trial, not so much by Breivik but by its inability to recognize the situation that produced him and its own dreary Scandinavian do-the-right-thing bourgeois misery. People may die, but it remains unseen whether they actually lived or not. The robotic pace of Norwegian society, as contrasted with the sharp mental clarity and sense of purpose that Breivik has, makes us understand exactly how this situation came about, and despite the emotional ending which favors pity toward the victims and the idea of “being strong by being weak” as one character describes it, shows us the actual topic and makes this film powerful.

Based on Åsne Seierstad’s 2016 book One of Us: The Story of Anders Breivik and the Massacre in Norway, 22 July embarks on a systematic telling of the tale that is precise down to the smallest details and captures, as in a Michel Houellebecq book, the contrast of the mundane and meaningless with huge and disturbing events. It does not look deeply into the motivations of Breivik, whose manifesto included “Conflict Avoidance And How To Avoid It” from Amerika, but sees him more as a reaction to this brain-dead and spiritually-numb “perfect” society.

A triumph of doubt in our equality-driven society manifests even in what many consider to be the pivotal exchange of the film between Breivik and his lawyer Lippestad:

Anders Behring Breivik: I’d do it all again if I could.

Geir Lippestad: You didn’t win, Anders. You failed.

Anders Behring Breivik: There will be others to finish what I’ve started.

Geir Lippestad: And we will beat you. My children and their children. They will beat you.

Although the lawyer tries to deliver this line with intensity, we can tell that he — the character, not the actor — has doubts, and even regrets, about how his society has turned out. Breivik puts Norway on trial by forcing its citizens to wonder what, after all, they are actually defending, and whether they enjoy living through it. As if the counterpoint this scene, the moments when politician Christin Kristoffersen (Maria Bock) puts her wounded child on a Skype call to her constituents shows us exactly what we need to know about the modern West: everything is for show, no emotion is real, and we have forgotten why we are going through the motions that we do, only that we have to keep the system afloat for our careers, self-importance, and fragile state of mental well-being.

As we recoil in the West from yet another diversity murder, this time the murder of Jewish people at prayer, Breivik seems refreshing in that instead of attacking the symptoms of Western civil war, he attacks the perpetrators. We see him gunning down people who are mostly Nordic and interacting with other Norwegians who seem to be play-acting at responding to him, as if acknowledging that they too are uncertain about their future. Danielsen Lie captures Breivik down to the facial expressions and mannerisms, and these scenes are scripted to show his thought process, finding himself reacting to new knowledge as he explores himself or acting consistently to advance his plan.

Perhaps many will be scared off by the “Netflix” production label to this documentary. Most of us are skeptical after several years of social justice propaganda from that media firm, but for some reason, this documentary manages a mix of views. Leftists will respond to the victim statements and see little else; the rest of us will sense the fear and trembling that runs through the West as we do the “right” things but can no longer believe in them, knowing that someday an avalanche of Breiviks or something worse will force us to wake up and change, or die.

Tags: anders behring breivik, asne seierstad, paul greengrass, shooting, utoya