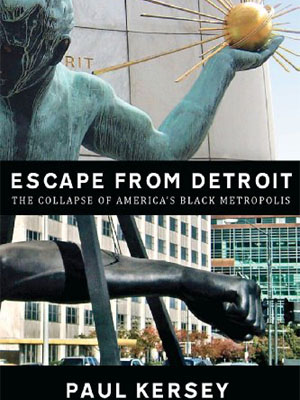

Escape From Detroit: The Collapse of America’s Black Metropolis by Paul Kersey

Escape From Detroit: The Collapse of America’s Black Metropolis

by Paul Kersey

374 pages, SBPDL Books, $12

We last checked in with Paul Kersey with his earlier book Hollywood in Blackface, an exploration of the radically different realities of race in movies, and in the physical world. For his next venture, he has launched an exhaustively-researched inspection of the inward collapse of Detroit, MI.

We last checked in with Paul Kersey with his earlier book Hollywood in Blackface, an exploration of the radically different realities of race in movies, and in the physical world. For his next venture, he has launched an exhaustively-researched inspection of the inward collapse of Detroit, MI.

Whether Kersey is right or not distills to a question of root causes. Many of us would argue that the cause of Detroit’s decline was abandonment by the middle class, which is inevitable once a mania for democratic equality becomes the norm, because democratic states focus on their poorest and least productive at the expense of the most productive in order to prove efforts are being made to enforce equality. A symptom of this, however, is a tendency to focus on ethnic minorities and civil rights at the expense of all other topics. This is a social conceit, not a political one; it’s popular to pity. The result is a tendency to favor the underdog at the expense of others, effectively bleeding a society dry for political objectives just as surely as the Soviets did before their collapse.

This may be the root cause, but in the meantime, Kersey asserts that the intermediate cause was racial strife — and he has the evidence to back it up. White middle class flight occurred only after the race riots of July 1967 which were the worst race riots in American history. Further, other factors do not adequately explain white flight. Conventionally, proponents of integration have blamed the collapse of the auto industry. However, this occurred in the 1970s and the exodus began immediately after the 1967 riots. Further, the suburbs showed no decline from the auto industry fallout; people simply found other jobs. While economic woes may be a contributing cause during the 1970s, the exodus started in the relatively prosperous late 1960s and was part of a larger pattern in which the white middle class moved out of the city for the suburbs as urban violence rose. After the riots, however, whites began to abandon the city wholesale.

Even more importantly, as this book points out time and again, for whatever reason that the white middle class left the city, the city then became ruled by African-American leaders for the African-American majority. This point is perhaps the most important one this book makes. If Kersey has time to do more analysis for a second version of this book, it would behoove him to include an economic history of the auto industry in Detroit to debunk this correlation that is often trumpeted as causation for Detroit’s decline. His analysis of black leadership may be more important, in that he shows how African-American poverty was not alleviated by African-American leadership:

Young was quoted as telling Rose in Detroit’s Agony:

In this country, Black people are victims of racism. It’s not accidental that cities around the nation that have the largest percentage of Blacks, have the largest percentage of poverty, have the largest percentage of crime, and the largest percentage of unemployment.

Immediately after making this assertion (which is true, because once a city goes majority Black, the Visible Black Hand of Economics takes over), Rose points out:

But in Detroit, Blacks aren’t just the majority. They’re the authority. They run the police, the courts, the schools, and city hall. But Black political power has not meant Black economic prosperity.

(245)

This paradox underscores much of the book. If white rule was oppressive, removing that white rule would alleviate the problem, we think. Clearly it has not, and Kersey will give any thinker a run for their money because his analysis of this gap is diligent and thorough. The evidence is overwhelming: since the advent of white flight and African-American government, we haven’t heard much from Detroit. The city is known worldwide for “ruin porn,” or photographs of its once-grand buildings and homes now in decay. Most people find such images depressing because they show abundant potential put to waste.

Kersey draws a distinction between Black-Run America (BRA) or the liberal plan for wealth transfer to poor black Americans at the expense of everyone else, and Actual Black-Run America (ABRA) which he uses to describe the leadership in Detroit and thus to illustrate the negative future offered if BRA succeeds. His thesis seems to be that African-Americans are incapable of self-government, and that a liberal plan to introduce Black-Run America will thus introduce Detroit levels of destruction across the United States. This idea contradicts the notion that most Americans are applying to race, which are expressed most clearly in the Kerner Report (253). This report, like most mainstream news sources and government, argues that since people are equal, the only source of African-American poverty is white racism. Further, the thinking goes, the solution is to spend large amounts of money on “Great Society” styled programs designed to bring equality to people through welfare, education and empowerment programs.

To defeat this mythos, which has the power of being an emotionally-satisfying and clear “easy” answer, Kersey digs deeply into the news articles and books about Detroit’s failings. His strength is as a researcher and contraster of ideas, and most of his arguments do not directly attack dominant paradigms but rather undermine them with clearly contradictory data and then explore those topics like tunnels through the vast mound of information on Detroit. At the end of those tunnels, he finds information that suggests a different truth, and emphasizes it by incorporating it into his narrative of the white middle class versus BRA and its advocates.

Much like the articles on this blog, Kersey is fond of quoting whole sections from his sources, and then explaining them in depth like a sociological analysis from primary sources. This fits right in with the funereal tone of this book as it presides over the decline of “The Paris of the West,” and allows him to approach it as an archaeologist trying to uncover the reasons for the failing of a once-great civilization. His sources often do the best explaining for him, through their inability to address certain possibilities or provide reasons for the decline; Kersey fills in for them using other sources, showing a truth emerging from reading between the lines and correlating similar data from different sources to provide a full picture of events.

In the 1960s, Disingenuous White Liberals (DWLs) like Mayor Jerry Cavanaugh thought that massive spending programs — redistribution of wealth — could maintain a steady peace between the white and black populations of the city. These dreams would spectacularly end in late July 1967 when Black people rioted, but the rest of the nation still clings to the belief that the government can redistribute money to the Black community to maintain the peace. (181)

The writing is compelling with strong and clear topic sentences, formidably readable explanations, and a refusal to drift off-course and ramble. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said of the copy-editing of this book, which is a bit rough at times and undermines his message. However, as these are blog posts gathered up and republished, it’s understandable that some errors would creep in since blog posts usually happen after work, during dinner, while phones and family members scream, at least for most bloggers. If SBPDL re-editions this book, it could use a rigorous edit to bring out its true power. As it is, the book is a joy to read that zips right along without running the reader into any incoherent parts. It doggedly stays on top of its argument, and owing to its nature as a collection of essays, is redundant, but without losing sight of what it is expressing. The effect here is like layers of an onion, in which each essay provides more clarity on what the previous one expressed.

As a good nationalist, I think Kersey has made a monumental effort here and has most likely identified the proximate cause of Detroit’s downfall, but there is more to the story. Whether African-descended people are capable of self-rule here or in Africa or not is not the question; the real question is, can diversity exist without destroying both the host (majority) and guest (minority) populations? History and current events show us that wherever diversity is tried, no matter what the ingredients, one population ends up impoverished and angry and the other population ends up in the role of perpetual giver, or being those from whom wealth is redistributed. Detroit shows us a valiant effort at making a city diverse and how, because diversity fosters distrust as Robert D. Putnam’s research shows, that valiant effort is doomed to failure because the resulting distrust creates blame, which in turn creates victimization, which in turn creates retribution through crime by the minority and abusive authority by the majority. This pattern repeats time and again even when both groups are white. African-descendend peoples, who evolved to adapt to an environment and social climate that did not emphasize rule-based civilizations, may also have additional challenges, but these are somewhat academic since diversity itself will undermine African-American self-rule and/or white stewardship.

It is important that these contextual musings come secondary to what Kersey so eloquently expresses in this book. When the Founding Fathers of the United States wrote about freedom of speech, this was the kind of book they had in mind. Speech that is universally praised or is inoffensive does not need protection; radical theses that undermine the wrong but popular ways in which we construct our society, on the other hand, not only need protection but require us to be extra-vigilant in promoting and analyzing theme. Whatever we think of the ultimate cause of Detroit’s decline, Escape From Detroit shatters the possibility of the convenient fairy tales we tell ourselves, and shames us into searching more diligently for the actual cause. In that it is a triumph and for those who can think outside of the government-media-populist narrative, one of the major book events of this year.

Tags: Books, detroit, paul kersey, race, white flight